The hips have a crucial role to play in the efficiency of the rowing stroke. Coach consultant Robin Williams explains more

The hips are a critical part of the power transfer in rowing, connecting the effort from the legs via the trunk to the spoon. The muscles around the hips, particularly the gluteals, are also strong in their own right so they can really help power production and unite the leg and the trunk movements. It can sometimes be hard to see if the transfer is fully working or not because individual back shapes and the geometry of body positions vary between individuals, as do flexibility and movement patterns. Nevertheless, they are important, so I want to look at ways we can use the hips well, what things can go wrong, and I want to also suggest some technical fixes.

The standard textbook sequence for the drive usually focuses on legs/trunk/arms and arms/trunk/legs for the recovery, with no particular focus on the hips. Perhaps we just assume that the ‘trunk’ takes care of the hips as well, but let’s look closer and see if that’s really the case. It’s all about avoiding energy losses and we all know what a bum-shove looks like at the beginning of the stroke, or a slumped posture at the finish. Both examples would mean that some of the leg drive is dissipated and never reaches the spoon, obviously reducing the propulsion of the boat, so how you sit matters.

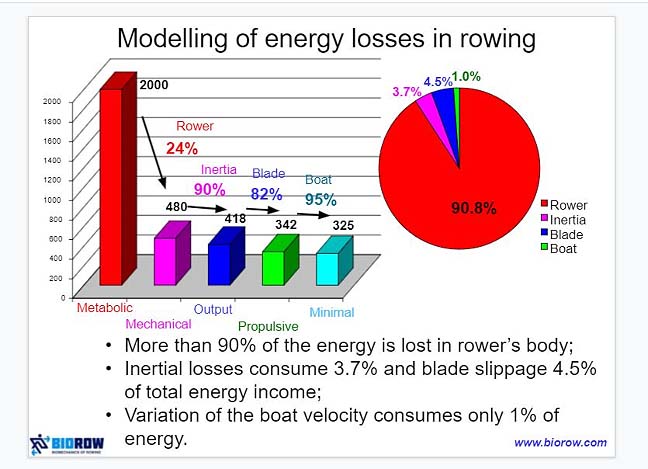

According to leading biomechanist Valery Kleshnev, the energy losses in rowing are mostly attributable to the rower, not the equipment. You can read more about this here and here.

Around 91% of losses are in the human body, and only 9% from the equipment and other areas (things like oar flex, gate rattle etc). Of those losses, the majority come from the trunk, with the hips at the lower end and shoulders at the top being the prime offenders.

The legs are a simple structure with few joints and are there for one thing – to push. The arms spend most of the drive straight and most of the recovery too, and since they are also two segments like the legs, their job is also reasonably clear. The trunk, however, can extend, flex, rotate, twist, bend, and has a complex system of tendons and muscles holding it all together – it’s no wonder energy gets lost along the way.

The catch

One typical problem at the catch is ‘tucking under’ at full compression, losing the lower back shape just at the moment you are about to load the stroke. Quite often the rower’s posture is fine until about three-quarters slide, but people with poor flexibility or technique lose that shape at full compression.

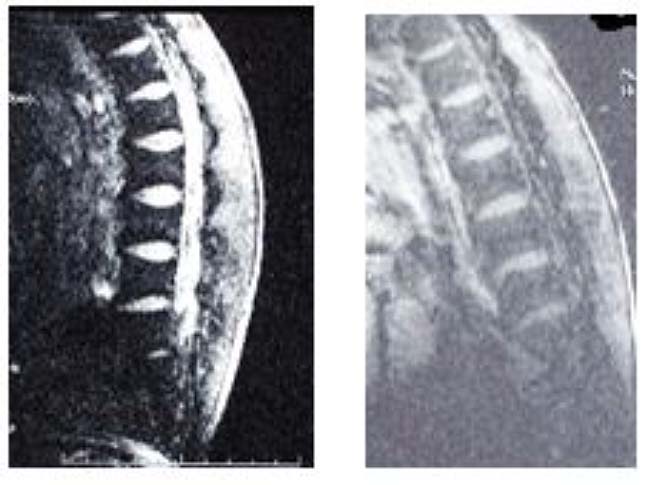

Apart from the technical inefficiency there is also a potential injury issue: the discs between the vertebrae can be overloaded locally and, in some cases, back problems can develop.

Professor Alison McGregor, of Imperial College, has made in-depth studies of this and as the left-hand slide shows, it is a worrying picture which can lead to disc injury. The fundamental correction is to sit up better in the hips. Apart from the health risk, a pelvic slump is also not good for transference of power. Imagine doing a clean in the gym and not setting your hips correctly first – the lift is severely compromised and it is fundamental in weights sessions. The right-hand slide shows a healthy alignment and is based on good hip position. So, in the boat it pays to sit well at the beginning and the best place to set up the correct hip angle is much sooner in the early recovery, preferably by a quarter slide.

Tip 1:

Breathe in and fill your chest as you arrive at full slide – it helps keep a tall posture and prepare the trunk for the load.

Tip 2:

It also helps to brace your stomach just before you push, as if someone was going to punch you there!

Bracing the stomach wall also engages the lower back muscles which reduces slumping and protects the back shape, like a corset around the base of the trunk. With that bracing the goal at the catch is to connect four points of contact: stretcher, handle, blade, and seat, and the hips and core tie them together.

Here are some drills to remind you:

Front end drills:

- Back downs: Get the hull moving backwards (stern-wards) and then do a roll-up from the finish to the entry at the front – the reverse load will try to pull the handle away from your fingers, so it encourages you to resist the stretcher pressure by bracing the lower trunk, and hanging off the arms.

- Rowing half crew, or use a bungee round the hull – again, the resistance makes the front end heavier, so instinctively people sit in a strong position. Your length should stay in a functional range.

- Inside-arm only rowing: for sweepers it makes your hips and trunk resist the twisting effect from the load.

- Hands down the handles: for scullers. The harder gearing forces you to brace low down.

- Legs-only rowing: this tackles the first part of the drive and, generally, people sit stable in the trunk as there’s no reason to over-swing or pull open at the front end.

Drills on the rowing machine:

- Rowing machine: try sitting on the machine, but with feet on the floor. This allows the pelvis to tilt forwards, as if standing up out of a chair. Then place one foot on the stretcher. Try rowing quietly with this one-foot arrangement, seeing if you can keep the pelvis forward at the front. Then put both feet on the stretcher like normal.

If you have mirrors around the rowing machine you can see how your posture looks at back stops, at quarter slide, half, three-quarters and full. This helps determine your effective length at the front end and finish, because this is where posture loss is most likely.

Developing the drive

So, let’s assume the hips have been good in the first section of the drive. In the first third of the stroke the hips are bracing the legs to transfer power to the oar, as you can see below.

In the middle third the hips open actively so, whilst still transferring leg power, they are now also contributing power themselves and help force the trunk angle to open.

By this point, the heel contact will be firm, legs and trunk working powerfully, and if you squeeze your glutes too this helps the ‘knees down, chest away’ movement. In the last third comes the arm pull and the hips play an important role here too, as we’ll see next.

Mid-stroke drills:

- No arms rowing: this reduces early pulling and persuades the hips and chest to fill out pressure against the leg push.

- Three-quarters slide and no arms finish: this effectively cuts off the first and last quarters of the stroke and leaves the middle half. Here the power is roughly 50/50 between legs and backs and is in the real power zone, so push the knees down hard and open the back strongly!

The finish

We looked at the finish in previous articles here and here, but I want to emphasise the hips here again. When it’s time to pull the arms in, it is important to be still generating power from the legs, and crucially, from the hips and trunk extension. If not, the arms can feel isolated and ultimately are too weak to make a strong finish on their own.

Once the trunk overtakes the hips, mid-stroke, gravity starts to win the suspension argument and it is common to see the rower’s weight back on the seat before the handle reaches the finish. Good hip extension can really help maintain effective pressure between the footboard and the handle and make it possible to sit back and also maintain suspension to the end.

This creates a lot of power for the finish and speed in the hull. Once the hip extension stops, you are relying on the shoulders and arms to keep pressure and of course they are less powerful than the hips and trunk. Those rowers who open their backs at the beginning of the stroke may initially feel a good connection, but it will slow the leg drive and make it hard to support the finish. You will see rowers who have ‘lost’ their hips trying to muscle a strong finish with the arms, but it’s a battle you won’t win. Certainly not when fatigue kicks in.

Finish drills:

- Fixed seat, trunk and arms suspensions: keep legs flat, reach forward with arms and trunk and try a stroke suspending 2cm off the seat. Aim to draw all the trunk through and arms, so the handle arrives at your ribs as you sit back down. You need to use your hips strongly to achieve this.

- A quarter-slide rowing: use 100% of your trunk swing and arm draw against just the last part of your legs and send pressure via your hips to the stretcher.

The recovery

The movement off the finish involves the hips too, of course. The aim is to create the upper body length for the next stroke, so, as the arms extend off the finish, the hips should naturally rock over, knees unlock and you should be set for the next one, with just the slide left and everything else organised and ready.

My article on the recovery explains how to get good speed from the boat during this phase of the stroke cycle.

How to strengthen your hips

These land training exercises will help you maintain or increase your hip strength.

Photos: Robin Williams