In a new series of articles Sam Boylett-Long talks us through the importance of resistance training to support a rowing programme. This first article discusses why resistance training generally is important and is followed by articles that focus on hypertrophy, strength and power

Rowing is a strength endurance sport with the requirement for a robust body that can produce force and effectively transfer it from the feet, through the trunk, arms and onto the handle. Whether you’re on an indoor rowing machine or on water the fundamental principles to generate an effective leg drive are the same.

As well as having good mobility around the hip and ankle, we also need strong knee and hip extensors to initiate and finish the drive, and a robust trunk and powerful shoulder complex to transfer the force onto the handle. During the stroke, the legs contribute 46%, the trunk 31% and arms 23% of the total force produced on average each stroke.

But why is resistance training important?

Even before diving into the benefits of strength training on performance, it must be noted that incorporating resistance training into your programme can improve robustness, bone mineral density, neuromuscular function, proprioception and injury risk. If we can reduce the sessions lost to injury, that is only going to increase the time available in the boat or on the rowing machine, offering increased protection against the demands of a training programme and ultimately improving performance.

From a performance perspective we know that force and power generating capacities are strongly linked with 2km rowing performance. Whilst strength has a stronger relationship with a fast and powerful start off the line, the average force per stroke is 65-70% of your maximal producible force. Thereby if we can increase the maximum force you can produce, we are driving up the submaximal forces and that 65-70% becomes greater. This means for the same level of relative effort we can express more force, improving stroke length and boat speed or ergo splits.

Strength training also promotes augmented endurance performance by improving exercise economy, delaying fatigue, and increasing anaerobic capacity and maximal speed. Exercise economy has been defined as the oxygen consumption required at a given absolute submaximal exercise intensity.

For example, many studies have concluded improved running economy after 8-14 weeks of heavy strength and endurance training with no significant changes observed in control groups just performing aerobic training. It must be noted that running economy was also improved after 6-12 weeks of explosive strength training and endurance training in runners which demonstrates that there are multiple ways to utilise strength training depending on your experience and training age (the total training time/experience you have in that aspect of physical training).

Types of resistance training

Now we know how resistance training can positively impact aerobic performance, what are the different types of resistance training and how do they differ?

Whilst resistance training can be broken down further into sub-categories, this article series will discuss hypertrophy, strength, and power-based training.

Hypertrophy

Hypertrophy and strength are tightly linked but we can tease them apart with the desired outcome. For example, if you’re goal is to put on lean body mass then a hypertrophy-focused programme coupled with a good diet will help you achieve that. Muscle hypertrophy in its simplest term means to increase the size of a given muscle or muscle group by increasing the cells that comprise it.

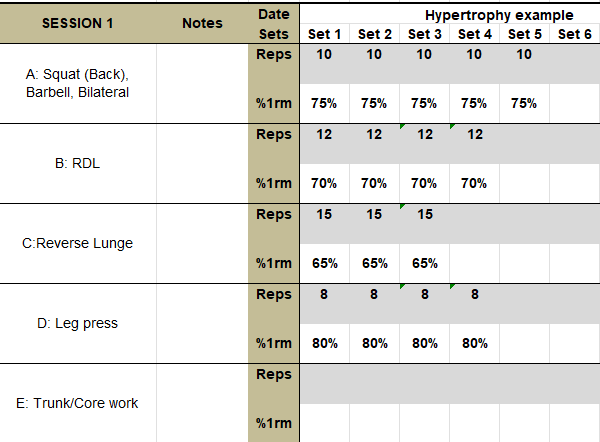

Here we have a generic lower body session directed at increasing muscle size of the quadriceps, posterior chain (hamstrings and glutes) and para-spinal muscles, completed with 90 seconds to two minutes rest between sets.

Example session:

Find out more about resistance training for hypertrophy here.

Strength

The goal of strength training is to increase the force a muscle or muscle group can produce during a contraction. We can train muscles to increase their force production in specific joint ranges at varying contraction types and speeds.

A common misconception with strength training is that you will put on mass just by completing a strength-focused programme. This can occur as a by-product of strength training but it depends on what the programme is biased towards as we can perform resistance training to increase force output without increasing muscle size.

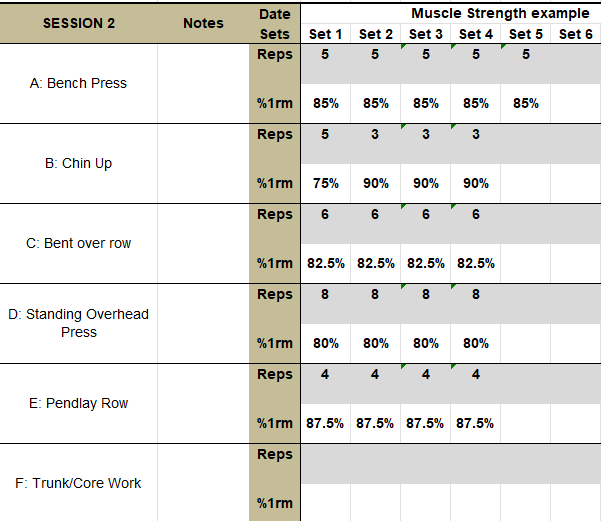

Below is a generic upper body session directed at increasing muscle strength in the chest, shoulders and back, completed with two to three minutes rest between sets.

Example session:

Find out more about resistance training for strength here.

Power

Power can be defined as a muscle or muscle group’s ability to produce force over a given period.

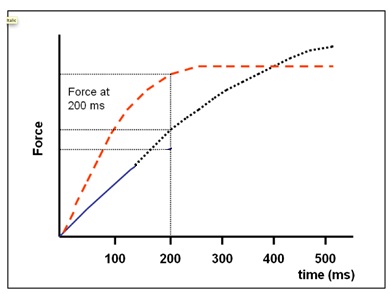

To illustrate this point, lets assume we have athlete A (red) and athlete B (blue/black) performing an isometric back squat. We can argue that athlete B is stronger over an indefinite period, clearly able to produce more force than athlete A who plateaus at 250ms. However, when we introduce a cut off time of 200ms it is athlete A who is more powerful and able to produce more force within 200ms.

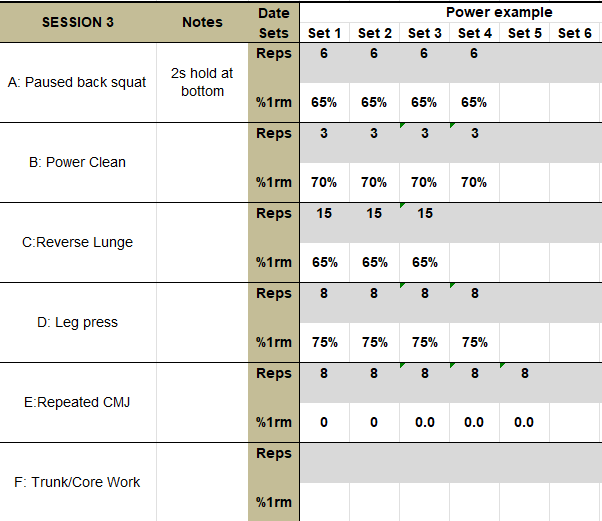

This is pertinent as most sporting skills or actions are constrained by time. A clear example being the start of a 2km where stroke rate is typically highest and a reduction in time between strokes demonstrates a higher reliance on power output. Below is a power focused session utilising lower loads with a high intent to move the bar fast across key movements.

Example session:

Find out more about resistance training for power here.

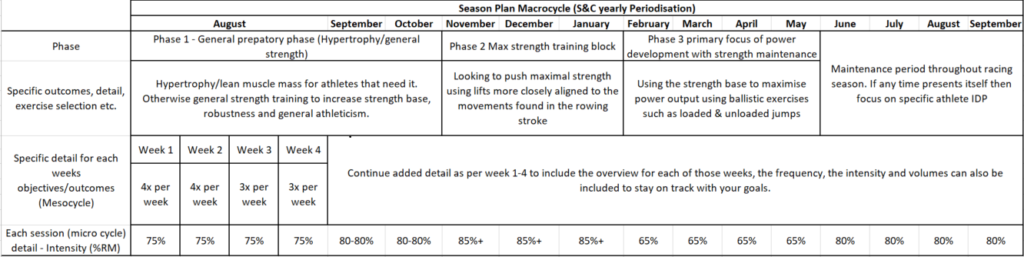

How do all these methods fit together within the rowing season?

Programmes typically follow hypertrophy, strength and into power-based training because power is derived by how much force we can produce in a specified time. If we don’t spend enough time building strength (force) then when we get to chasing power we have a limited supply of force to reply upon. Essentially, one characteristic underpins the next and so on.

Predominantly, your resistance training programme will be shaped by your training age, previous injury history, season structure and style of rowing/racing. For example, if you and your coach are trying to adopt a high distance per stroke race strategy using a lower stroke rate, that will require a different programme to one whose plan is to rate quickly.

Whilst there will be nuances based on the above, generally the flow of a training cycle will begin in the pre-season or early winter. In this phase I would look to focus on hypertrophy for those who need to add some lean body mass, otherwise building an athletes strength base.

I would begin working at a lower percentage of one rep max (~70%) and build through until December, or if you re-test and are content with your base strength then you should re-establish the outcomes of the programme. This could potentially include power work earlier on in the season.

Between Jan and April, I would have a primary focus shift where we aim to improve the athlete’s power and use of the strength base we built in the previous quarter of training. It would be important at this stage to re-evaluate the training programme and how much force you are able to produce. Again, if you aren’t happy with your progress, or force outputs then it might be more beneficial to spend more time strength training.

From the end of April through to the end of the season, where racing takes priority, I would suggest finding a strategy to optimise performance based on the number of weights sessions, their frequency and your freshness. This way, you can maintain the qualities you developed throughout the year, reducing the drop off throughout the racing season.

Next article: Resistance Training Series #2: Training for hypertrophy (increased muscle mass)

Photo: Dean Drobot/Shutterstock.com