What can we learn from Olympic rowers’ training programmes? Sarah Moseley from the GB Rowing Sport Science Team explores the research and shares advice for all rowers

Olympic rowing is a power endurance sport with several physical, technical and anthropometric requirements. Every rower is different, and each possesses characteristics that contribute towards individual or crew-boat success – in short, there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach when it comes to athlete development.

Rowing machine, water and weight-room assessments play an important role in helping to identify the physical strengths and limitations of an athlete.

Through regular testing, targeted changes can be made within a programme to make a strength a super-strength and to improve on a weakness.

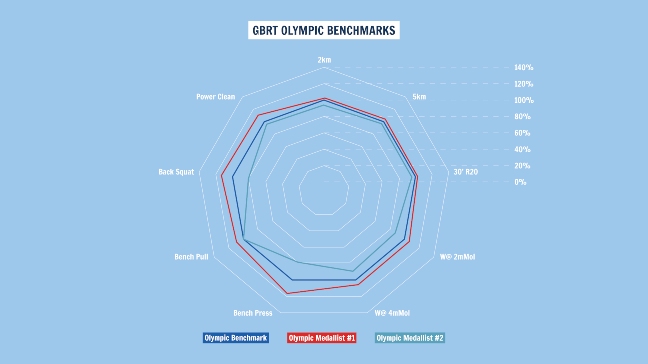

Graph 1 (below) outlines a range of physical performance assessments completed by two medallists from the 2016 Rio Olympics. The graph demonstrates two different profiles, both of which led to successful performances – in this case, an Olympic silver medal.

Olympic medallist #1 exceeds all of the Olympic physicality benchmarks, however Olympic medallist #2 exceeds only one out of nine of the benchmarks.

While physical parameters are easier to assess, psychological and technical characteristics should also be considered when reviewing athlete performance.

1 – Aerobic capacity

VO2max is the highest rate at which oxygen can be extracted, transported and consumed in the process of energy production. It is a metric which unites aerobic capacity in endurance sports.

Rowers with a higher VO2max can deliver more oxygen to the exercising muscles, allowing them to work at a higher intensity for longer. While directly measuring an athlete’s VO2max requires expensive laboratory equipment, many studies have demonstrated that a faster 2km performance on the rowing machine also indicates a greater aerobic capacity.

How to improve your aerobic capacity

Novice and amateur athletes

Simply doing more training volume will help to improve your VO2max. High-volume steady-state aerobic training will help to develop long-term improvements through peripheral adaptations i.e. increased aerobic enzymatic activity, capillary numbers and mitochondria density.

If you don’t have time to do more volume, there are some targeted sessions which can achieve short-term central adaptations i.e. increased heart size and strength.

Try including one session per week working at, or slightly below, maximum effort, for example high-intensity interval training. In these sessions you should work close to maximum for short periods of time followed by a period of recovery for example:

- Three minutes hard (approximately 2km pace) followed by three minutes of light rowing repeated three to six times.

Highly trained or elite athletes

VVO2max will plateau after several years of full-time endurance training, therefore subsequent improvements are owing to other factors including improved aerobic threshold, anaerobic capacity and power development.

Aerobic threshold

Olympic rowing performance is dependent upon the capacity of both the aerobic and anaerobic energy pathways. During a 2,000m race, approximately 75% of energy is derived from aerobic metabolism and approximately 25% is derived from anaerobic metabolism.

Improving the aerobic threshold is essential to enable athletes to work at a higher intensity

During aerobic metabolism, your body creates energy by using a combination of carbohydrates and fats in the presence of oxygen. When the aerobic system cannot keep up with the energy demand of the race (i.e. during a sprint start or sprint finish) anaerobic metabolism kicks in. During anaerobic metabolism, the body uses carbohydrates to supply the additional energy demand, and blood lactate (a by-product of carbohydrate metabolism) is produced faster than it can be cleared, resulting in an accumulation of hydrogen ions and subsequently muscle acidosis.

The ‘aerobic threshold’ is the point during incremental exercise when your body shifts from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism. Improving the aerobic threshold is essential to enable athletes to work at a higher intensity before accumulating high levels of lactate associated with anaerobic metabolism.

Measuring blood lactate is the typical monitoring tool for assessing the aerobic threshold in elite rowing. Highly trained athletes generally accumulate less lactate than amateur athletes at a fixed sub-maximal workload as a greater proportion of energy is produced through aerobic pathways i.e. they have a better aerobic threshold.

Strength training can prevent common rowing injuries by correcting muscular imbalances

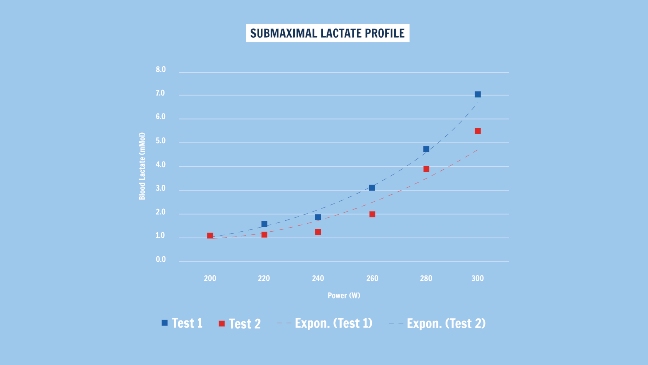

Graph 2 represents a typical blood lactate response to a sub-maximal incremental step test. The graph demonstrates a reduction in blood lactate at each power output during test 2, suggesting an improvement in the aerobic threshold. This is due to a reduction in the rate of lactate production and an ability to clear lactate more effectively.

The power achieved at 2 and 4mMol of lactate is highly correlated with elite rowing machine performance.

2 – Strength and robustness

Strength training plays an important role in rowing performance.

Firstly, strength training (low repetitions with high load) improves neuromuscular function resulting in improved muscle fibre recruitment, synchronicity and rate of muscle fibre contractions. Furthermore, strength training can prevent common rowing injuries by correcting muscular imbalances often seen in sweep/bow-side rowing or trunk and lower back stabilisers.

“Addressing movement inefficiencies will better enable the application of power to boat speed”

Sam Boylett-Long, UK Sports Institute Strength and Conditioning Coach working with the GB Rowing Team, shares his recommendations, saying: “For recreational rowers, try integrating strength training e.g. twice per week into your weekly programme.

“A total body workout that uses compound lifts and targets all major muscle groups would be appropriate to start with and, once you have established a solid base, you can focus on muscle groups that are more specific to the rowing stroke.”

For highly trained or elite athletes, he advises: “Strength-focused training blocks can be incorporated into your programme if strength is considered to be a limiting factor.

“Targeted strength blocks of eight to 10 weeks in duration, with three strength workouts per week can be completed, ideally, with a small reduction in endurance training volume, throughout the year e.g. during the winter phase or during periods of injury.”

Sally Brown, Senior Physiotherapist with the GB Rowing Team, says: “Athletes often have a high physiology base level, with training focusing on further improving aspects of their physical performance. However, attention to the biomechanical movement is also needed.

“Addressing movement inefficiencies will better enable the application of power to boat speed.”

She adds: “Athletes with sub-optimal physical qualities risk unconsciously compensating to try and find a way to achieve the desired movement objective.

“If the loading on the body exceeds its ability to compensate, injury may occur or performance outcomes may be impacted, therefore regular robustness should be incorporated into a programme to address mobility, motor control, work capacity and strength.”

Photo: Nick Middleton