Training while unwell can do more harm than good, potentially prolonging illness and derailing performance goals. So, how can you determine whether you’re fit to train? British Rowing Performance Development Academy Doctor, Alex Woods, provides a brief summary.

How does training work?

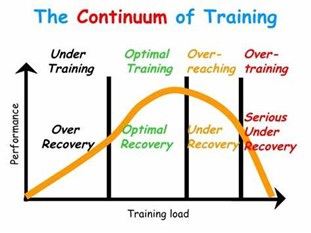

As Performance Development Academy Physiotherapist Katherine Vials explained in her recent article on Managing Injury, getting physiologically stronger and faster involves a careful balance between training/loading and recovery, to allow the body to undergo adaptation, as shown in Figure 1.

Therefore, effective training is about managing the loads that we are putting on our bodies. The key message to understand about training and illness is that being ill affects our bodies’ ability to recover – and therefore also our ability to ‘adapt’ in response to training. If our bodies don’t adapt, then there is rarely any benefit to be gained from doing the training.

Why do athletes consider training while sick?

Athletes often feel immense pressure to keep training, even when their body is signalling that it needs rest. Common reasons why people mistakenly think they should keep training include:

- Fear of falling behind: The worry that missed sessions will affect progress.

- Perceived weakness: Concerns about how teammates or coaches view them.

- Underestimating the importance of rest: A belief that illness isn’t serious enough to warrant a break.

However, ignoring symptoms and continuing to train can suppress the immune system further, and delay recovery. I n the worst case, it can even lead to ’overtraining’ syndrome.

Understanding illness and the immune system

Training places stress on the body, including the immune system. Intensive or prolonged exercise temporarily suppresses immune function, especially during the 3-72 hours post-training. This period is often referred to as the ’open window’ for illness susceptibility. During this time, viruses and bacteria can take advantage of the body’s weakened state.

Scientific evidence suggests that infections, particularly of the upper respiratory tract, are common in athletes undergoing heavy training loads. This is particularly a risk in winter months due to the increased amount of time spent indoors with other people. Infection risk can be exacerbated by inadequate recovery, poor nutrition, or stress.

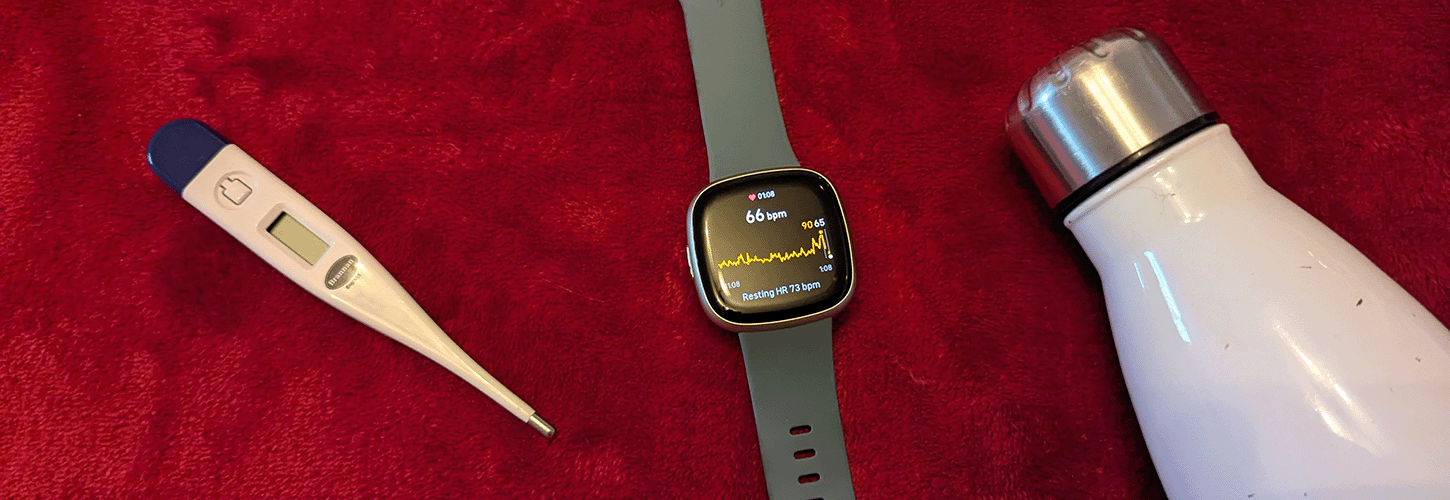

Monitoring your body: Key tools

Learning to understand your own body and how it responds to the stresses of training alongside day-to-day work/study and life is critical for balancing training and recovery. Here are some effective areas you can monitor to get early indicators that things are amiss:

Heart rate

Measure your resting heart rate in the morning. Consistent elevations compared to your “normal” can signal illness, stress, or under-recovery. There is some evidence that looking at the difference between lying and standing heart rates provides a more informative view of how your body responds to a stress.

You can also monitor heart rate recovery after exercise. Slower recovery to your normal baseline may suggest that your body is struggling to recover.

Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

My personal favourite is RPE, which is a subjective measure of how hard training feels. Whilst this sounds obvious it takes a reasonable amount of effort to gain insight into how you normally feel during different types of training.

Rowing training is attritional and it’s easy to lose sight of how ‘normally tired’ feels. If your usual intensity suddenly feels much harder, it may indicate illness or under-recovery.

Research by Saw, Main, and Gastin (2015) found subjective measures like RPE can be more sensitive to changes in health than objective metrics. Gaining good insight into what is normal for you with RPE can really help guide return from illness to full training.

Sleep

Poor sleep weakens the immune system. Track your hours and sleep quality, making an honest view of your own sleep hygiene – aiming for consistent and restful sleep.

Hydration and nutrition

Dehydration can impair performance and recovery. Aim to replace fluid losses post-training; 1.5L of water for every 1kg lost is a good rough measure. Nutrient deficiencies, especially in Vitamin D, Vitamin C, and Iron, can also weaken immunity – rowers generally require high volumes of balanced diets to help adapt optimally to training.

Check out these simple nutrition and hydration solutions to maximise your recovery after training and racing.

How to reduce illness risk

As should be obvious now, recovery is as important as training. Over-training is not necessarily just doing too much exercise in absolute terms. It’s the equivalent of under-recovery, as it’s doing too much exercise for your body to recover/adapt from.

To help reduce illness risk:

- Prioritize post-training recovery: Complete nutrition, hydration, and rest tasks after every session.

- Optimize nutrition:

- Consume carbohydrates during and after training to dampen inflammation and protect immune function. Athletes often lose site of how much time it takes from the end of a session to finish a debrief, put the boat away, get changed etc. before they start refuelling. If that rings true, try to carry some easy to eat food with you to consume immediately after training.

- Include foods rich in Vitamin D, Vitamin C, Iron, and Vitamin B12.

- Incorporate probiotics through yogurt or fermented foods to support gut health.

- Practice good hygiene: Wash your hands regularly, avoid sharing water bottles or food, and minimize contact with sick individuals during the ’open window’.

- Manage stress: High life stress can weaken the immune system, making you more susceptible to illness. Incorporate relaxation techniques such as mindfulness or light reading.

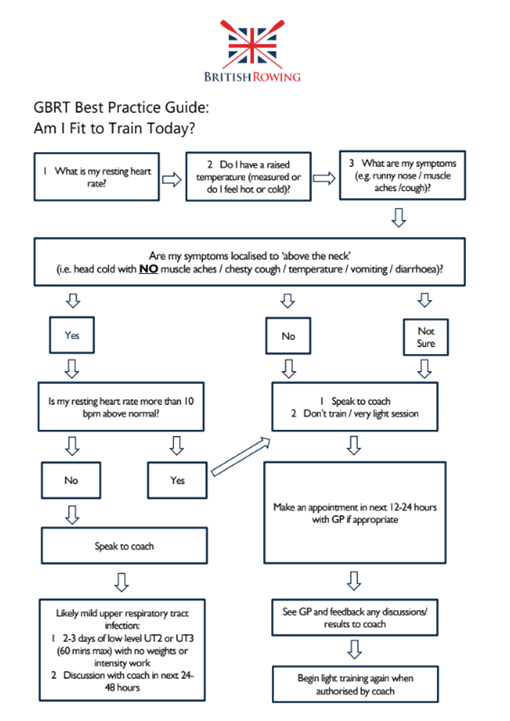

When to rest: GB Rowing Team Best Practice Guide

British Rowing has developed the simple flowchart shown in Figure 2 to help rowers consider whether they need to adapt their training to improve recovery.

This approach considers symptoms uses the ’neck rule’ as a basic guideline:

Above the neck: Symptoms like a mild sore throat, runny nose, or nasal congestion may allow for light exercise, but only if energy levels are adequate.

Below the neck: Symptoms such as chest congestion, a persistent cough, fever, muscle aches, or fatigue are clear indicators that you should rest.

Text Box: Quick Checklist: Am I fit to train today?

- Do I have symptoms below the neck (e.g. fever, chest congestion, body aches)?

- Is my resting heart rate elevated?

- Am I feeling unusually fatigued?

- Is my sleep quality poor?

- Does exercise feel much harder than usual (higher RPE)?

If you answered “yes” to any of these questions, take a rest day. Your body will thank you, and you’ll come back stronger.

Returning to training after illness

When returning to training after illness, patience is key. Start slow and progress gradually to avoid relapse. Here’s a guide for easing back:

- Start with light exercise: Gentle sessions at 50-60% of normal intensity.

- Listen to your body: Monitor heart rate, RPE, and symptoms closely.

- Prioritise recovery: Extra sleep, hydration, and nutrition are critical as your body regains strength and returns to ‘normal’.

- Take 2-3 days post-illness: Once symptoms resolve, give yourself an extra 48-72 hours of rest or light training to ensure full recovery and avoid spreading illness.

The bottom line: Train smart, not just hard

Pushing through illness might seem worthwhile in the short term, but it often backfires. Rest days are not a sign of weakness – they are an investment in long-term performance. By learning to recognise early signs of illness, monitoring your body, and prioritising recovery, you can train smarter, stay healthier, and perform better when it truly counts.

References

Saw, A. E., Main, L. C., & Gastin, P. B. (2015). Monitoring the athlete training response: Subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(7), 515-519.

Nieman, D. C., & Wentz, L. M. (2019). The compelling link between physical activity and the body’s defense system. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 8(3), 201-217.