GB Rowing Team athlete Kyra Edwards, who is also a part-time Research Fellow in medical statistics at University College London, talks about the findings of her latest research project, and how she and others in the team see the menstrual cycle.

Menstrual cycle basics

You can read a detailed explanation of the menstrual cycle here but for the purposes of this article, the key points to know are:

- Menstruation occurs from the ages around 13 to 50.

- The cycle starts with a period, which lasts around five days

- Several hormones such as oestrogen and progesterone fluctuate through the cycle.

- A normal cycle length is considered between 21 and 35 days.

The impact of the menstrual cycle on performance

Two-thirds of female Olympic athletes across various sports say that the menstrual cycle affects their performance.1 Two-time Olympic Champion Helen Glover says, “We’re scraping our fingernails for those halves of a percent speed gains. Knowing more about the menstrual cycle would definitely make a positive difference”.

The menstrual cycle impacts almost all women who menstruate negatively and quite profoundly. For example, women are 7% more likely to miss a competition on their period than at any other time.2 Yet we still know so little about the mechanisms that underpin these differences and what we do know in academic literature often doesn’t make it into the hands of the general public.

My research into heart rate fluctuations across the menstrual cycle

I have an academic paper in the prepublication stage on the fluctuations of Resting Heart Rate (RHR) and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) across the menstrual cycle.

RHR and HRV are commonly used as a measure of health, fatigue and readiness for training.3 For us in the GB Rowing Team, the first question our team doctor and support staff ask when we seek advice from them if we’re feeling unwell is, “What is your resting heart rate?”. A lower RHR is considered optimal and an indication that your body is more recovered.3 On the other hand, a higher HRV is seen as positive as it is a sign of your body’s ability to handle greater levels of training stress.4 Both are measures of our body’s ability to balance the ‘fight or flight’ versus ‘rest and digest’ pathways of our autonomic nervous system.5

Historically, it has been assumed that RHR and HRV are as constant in women as they are in men. This is most likely because only 6% of sports and exercise research uses female-only cohorts.6

Our study aimed to develop an understanding of how RHR and HRV may differ for females and build to a continuous picture of these over the cycle. Working with Flo, a menstrual tracking, health and wellbeing app with over 57 million active monthly users, we investigated the relationship between RHR, HRV and the menstrual cycle amongst a random sample of over 1,000 people who had a wearable device such as an Apple Watch or FitBit.

What we found

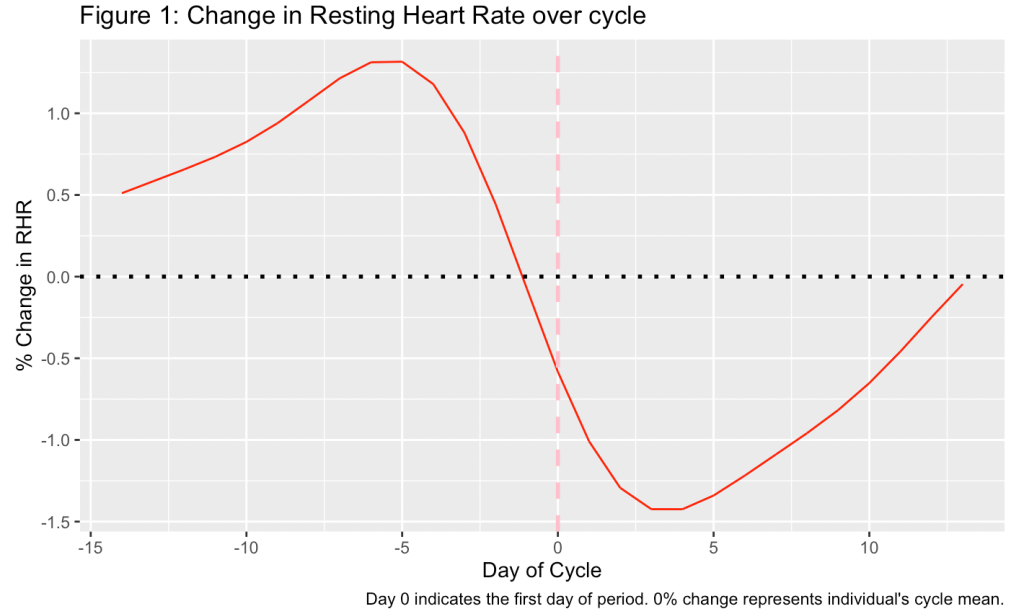

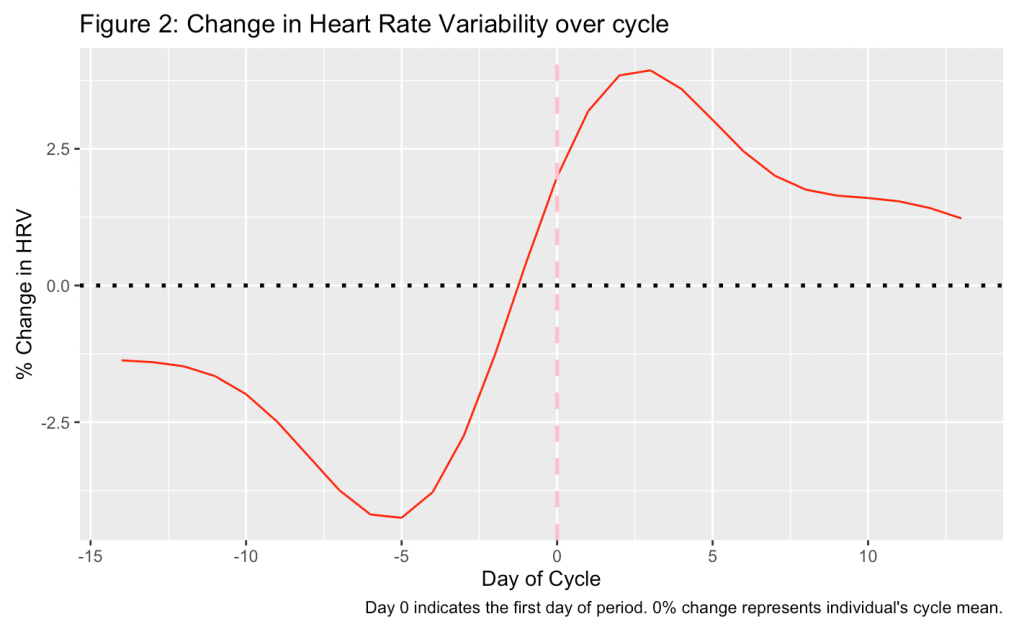

Unsurprisingly we found that women who menstruate naturally experienced fluctuations with a range of over 3% in their RHR and over 6% in their HRV. RHR and HRV were optimal on the first day of a period, effectively a woman’s ‘best’ time to perform on average. Interestingly, these markers become increasingly worse through the cycle – by 0.2% and 0.4% on average per day for RHR and HRV respectively. These rapidly reset four days before the next period, returning to the same baseline as the start of the cycle at a rate of 0.7% and 1.7% of RHR and HRV respectively.

Ultimately, the day of your cycle will narrowly impact your RHR and HRV. If your RHR is 60 at the start of your period, it will be approximately 62 four days before your next period. For HRV, if you have an HRV of 150 at the start of your cycle, this will be approximately 159 four days before your next period, regardless of any other fluctuations caused by fatigue or ill health.

It is important to note that previous similar research has found that the use of hormonal contraceptives will minimise these fluctuations.7

Comparisons to other research

The results we found align with a survey of Tokyo 2020 Olympic athletes across several sports who were asked when the most favoured time of their cycle to perform was. Notably, the majority responded with the time “just after their period”.1 Although this doesn’t exactly correspond with the optimal time of RHR and HRV, it does make sense that period symptoms such as cramps, bloating or fear of leaking will conceal these potential ‘gains’. When these subside you feel the benefits, and this would be the time just after your period.

On that point, symptoms of a period are often so bad that another study found that four in five women will be less productive during their period.8 What is important to note here is that women perceive different parts of their cycle as more or less optimal for performance and these relate to tangible bodily fluctuations. I asked a few of my teammates if they felt different across their menstrual cycle. Olympian Chloe Brew said, “On the days leading up to my period I feel more tired, and my body and mind become more sensitive.” Whether you are a professional or recreational athlete, having a menstrual cycle will likely affect your body and mind and maybe even your attitude toward a training session, and that is normal.

Communicating about the menstrual cycle in the GB Rowing Team

In the GB Rowing Team we have open communication about our menstrual cycle and how it might be affecting us. We’re lucky that our support staff are invested in making progress in this area of women’s health. As a team we are involved in a world-leading study, called Project Minerva, which aims to develop an objective and subjective understanding of how the menstrual cycle impacts our bodies’ response to training stimuli.

A team are tracking our cycles, using saliva samples to measure our hormones and heart rate data to explore whether our heart rate zones respond differently to sessions across the cycle. This is exciting for us; talking to teammates it seems like there will be some interesting findings. 2022 World Champion Heidi Long has already noticed the influence of her cycle on her training. She found that, “In the days before my period I struggle to lift the weight in the gym that I can lift on the first few days of my next cycle with ease. This is only a few days later.” Hopefully, this study will be able to shed more light on whether this is true for most women or allude to other mechanisms at play.

Conclusion

Ultimately, right now we lack detailed and concrete research on the impacts of the menstrual cycle. What it does say is that women aren’t constant, and our menstrual cycle will have some level of impact on your body, mind and emotions.

The best way to understand how the menstrual cycle impacts you is to note the dates of your periods, perhaps using an app like Flo, and by keeping an eye on factors such as heart rate, symptoms or emotions that change across the cycle.

Also, speak to women around you, it can be empowering to find out that they feel the same way as you and it’s most likely that they do!

Key takeaways

- Be conscious that your menstrual cycle effects your whole body, even fundamental functions of your heart health.

- Your menstrual cycle will affect all the women around you too, so reach out to them!

- Use your smartphone to track your cycle, be aware of and log symptoms and make note of ones that keep occurring for you!

Note: I recognise that not all people who menstruate identify as women, but I have used the term ‘women’ in this article because of the lack of research in female-specific populations.

Bibliography links

- McNamara A, Harris R, Minahan C. ‘That time of the month’ … for the biggest event of your career! Perception of menstrual cycle on performance of Australian athletes training for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2022 Apr 12;8(2):e001300. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001300. PMID: 35505980; PMCID: PMC9014077. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9014077/

- Bruinvels G, Goldsmith E, Blagrove R, et al. Prevalence and frequency of menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with availability to train and compete: a study of 6812 exercising women recruited using the Strava exercise app. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2021;55:438-443. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/8/438

- Brian Olshansky, Fabrizio Ricci, Artur Fedorowski, Importance of resting heart rate, Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1050173822000731

- Heart rate variability: How it might indicate well-being. Harvard Health Blog, December 1, 2021. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/heart-rate-variability-new-way-track-well-2017112212789

- Christopher H. Gibbons, Chapter 27 – Basics of autonomic nervous system function, Editor(s): Kerry H. Levin, Patrick Chauvel, Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Elsevier, Volume 160, 2019, Pages 407-418. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780444640321000278

- Cowley, E. S., Olenick, A. A., McNulty, K. L., & Ross, E. Z. (2021). “Invisible Sportswomen”: The Sex Data Gap in Sport and Exercise Science Research. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 29(2), 146-151. Retrieved Nov 1, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2021-0028. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://journals.humankinetics.com/view/journals/wspaj/29/2/article-p146.xml

- Sims ST, Ware L, Capodilupo ER. Patterns of endogenous and exogenous ovarian hormone modulation on recovery metrics across the menstrual cycle. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2021;7:e001047. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001047. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://bmjopensem.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001047

- Schoep ME, Adang EMM, Maas JWM, et al. Productivity loss due to menstruation-related symptoms: a nationwide cross-sectional survey among 32,748 women. BMJ Open 2019;9:e026186. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026186. Accessed 1 November 2023. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/6/e026186

Photo: Darren Whiter.