On paper, the process of getting from the point of injury to returning to full training can look straightforward.

In reality, that journey can often be emotional, challenging, and difficult to navigate.

British Rowing Performance Development Academy Physio Katherine Vials explains what you can do to recover as efficiently and quickly as possible – and how injury can even help you become a better rower!

What is an injury?

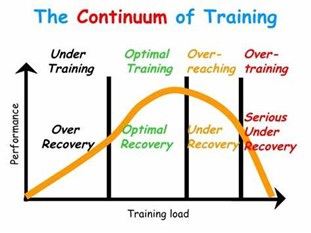

Getting fitter, stronger and faster involves working as closely as possible to the fine line between training/loading and recovery, as shown in Figure 1. It is about managing the loads that we are putting on our bodies.

Injuries occur when structures are taken beyond this tolerance, which has been described as “disruption of the mechanical order of the biological system”1.

What does an injury feel like?

Most injuries will be obvious, but they come in all shapes and sizes. How your injury feels like therefore depend on the structure(s) that are affected. As well as pain, symptoms may include stiffness, pins and needles or numbness, or even disturbed sleep. The important thing is to listen to your body. If something feels different, pay attention.

Why do injuries happen?

It’s complicated!

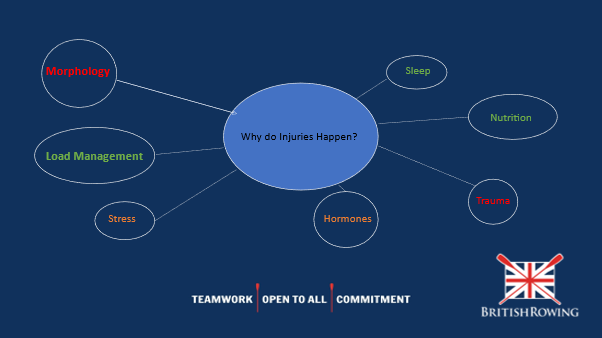

There are some components of injury that are not in our control (identified as red text in Figure 2), such as trauma and ‘morphology’, which is our individual anatomy. In some cases our movements can be affected by how we are made, and this can lead to injury.

Then there are factors such as stress and hormones (shown in orange in Figure 2), which may not be easy to change either. However, we need to understand how they might affect our musculoskeletal system. Stress and hormones are part of life, and in female athletes the presence of menstrual cycles is an important sign of health. Although these hormones won’t affect physiology, it is important to track menstrual symptoms to understand any links to signs and symptoms of injury, and how your body might react to training at different points in the menstrual cycle.

Whether we are male or female, our bodies are unable to tell the difference between the hormones released from stress and those released from intense exercise, so it is also important to understand how this can affect our ability to adapt to training.

The good news is that there are lots of possible contributing factors that you can be in control of – so you should ’control the controllables’ (shown in green in Figure 2). The benefits of sleep hygiene and quality, the what and when you eat around training, and managing the loads are all powerful ways to try and stay on the right side of injury.

What should I do if I think I’m injured?

It is completely normal to feel apprehensive about admitting that you might have an injury. This may be through the fear of missing training and loosing fitness, or potentially losing a seat in the boat.

Early intervention generally means that you are going to get better quicker, so if there are signs and symptoms that your body is not tolerating the load, then try and start an early conversation with your:

- Coach

- Physio/doctor/other heathcare professional

- Team mates

- Parents/guardian.

Can I keep training when I’m injured?

Generally, YES!

In the early stages of injury, it is usually necessary to reduce the training load, and this will mean that you won’t be rowing initially. Swimming and cycling are often useful options for maintaining fitness whilst ‘deloading’, provided they are suitable for your injury. A physio or doctor can help with load management and provide a plan that is specific to you and your injury.

But if you are in pain, NO!

Training into pain is highly likely to make the injury take longer to recover. It also increases the risk of worsening the injury. Both of these are going to keep you out of the boat for longer.

How long will my injury last?

This will depend on a number of factors. A physio can help estimate this by understanding the nature of the injury.

Healing times will depend on the structure affected, your age, injury history, and the length of time you’ve been having symptoms. They will also vary according to the level you are rowing, how much training you are doing, and how many years you’ve been training. For example Olympic squads and club rowers are likely to have different recovery time expectations. But whatever type of rowing you’re doing, early detection is key is recovery time.

Phases of return from injury

Phase 1: Resolve your symptoms whilst maintaining fitness

An assessment by a physio will provide information to help understand what is causing symptoms. This enables everyone to set expectations for healing time frames and how the recovery process is likely to go.

During this phase, it is also important to look for any learnings that sustaining the injury may provide. In particular, are there identifiable contributing factors to the injury? Rehab training can be an amazing opportunity to work on areas that might need more attention.

Phase 2: Reload

This stage is often not linear because you are working on the edge of progression without stepping into overload. The rate of progression will depend on the suspected injury and the individual athlete.

To enable your body to adapt to an increase in load, consider adding in just one of the three components of frequency, intensity, and duration at a time, with intensity generally being the final addition.

Summary

Injuries – although common – can be frustrating.

But identifying signs and symptoms early, and communication with and support from a health care professional can lead to a quicker recovery.

Finding your support network can make this process easier along with understanding the possible contributing factors… controlling your controllables.

Due to the volume, repetition and loading involved in rowing, small mechanical or strength deficits can, over a period of time, lead to overload and therefore an injury. One positive outcome from working through the rehab process is that it provides an opportunity to find out more about what these might be. You can then make those changes and work on any weaknesses, which may ultimately make the boat go quicker!

[1] Kumar S. Theories of musculoskeletal injury causation. Ergonomics. 2001 Jan 15;44(1):17-47. doi: 10.1080/00140130120716. PMID: 11214897.