What can we learn from how elite teams approach success? Dr Mark Homer explores the key areas

Following the Rio 2016 Games, UK Sport – the strategic leaders for Team GB Olympic sports – began an initiative which required governing bodies to provide a detailed explanation of what is required to win an Olympic gold medal in their sport. Using the 100m as an example, a male athlete running 9.54 (a new world record) would all but guarantee a gold medal in Paris 2024. The sport would then need to provide the required to understand what it takes to run that fast by breaking the event down into the factors that determine it.

Organisations approached this task in different ways, a tactic encouraged by the funding body. For some (eg. the marathon), the highly objective time or distance-based methods for picking a winner made this task relatively more straightforward, particularly for highly repeatable sports in a ‘closed’ environment. For invasion games, combat sports or ‘judged’ events (eg. rhythmic gymnastics) things were more complex and required a more subjective approach.

Isolating and ranking the determinants of performance, in order to explain success in rowing, fell somewhere between these two extremes. To the uninitiated, 2,000m of uninterrupted straight-line racing might seem cut-and-dry. However, trying to explain the effect of wind direction and crew dynamics on performance soon shows that there is not just one single formula that provides an explanation of victory.

As head of High-Performance Science & Medicine at the time, it was my responsibility to produce the GB Rowing Team’s version of this model. This task took me on an interesting journey and, ultimately, made me look at the sport in alternative ways, rather than only using the scientific approach I favoured as a physiologist.

1 – Rowing performance

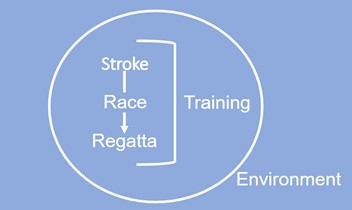

The diagram above represents a scaled back model of what was eventually produced. In essence, success in rowing is dependent on being able to deliver a technically proficient and suitably powerful rowing stroke in unison with the rest of the crew. This needs to be done around 250 times in a row to complete a race. This must be improved two to three times over the course of a regatta in order to be in and win the A final.

2 – Physiology

In order to deliver a world-beating collection of races, an athlete and their crew must be able to complete the training required. Finally, this all needs to be underpinned by an environment containing the people, facilities, and culture to facilitate consistent world-class performance.

Behind this headline view, there was a mix of objective and subjective qualities that the team believed were crucial to gold-medal winning performance. These included anthropometric (being tall with long limbs provides a biomechanical advantage that contributes to the stroke element of the above model), physiological, biomechanical, and psychological amongst others – many of which bridged several of the performance determinants discussed above. While this model was constructed with elite performance in mind, many of its components are applicable to anyone who competes in the sport – no matter what the level.

“Training smart is key to getting the most out of your physiology and being the fittest you can be”

As we all know, physiology plays an enormous role in determining rower success. This was something I was comfortable with, and I had the numbers to back it up. A large aerobic capacity and ability to utilise it make an enormous difference to the race element of the above model and is supported by racing evidence and research. A large engine also contributes to the recovery between races and ability to repeat a performance as the regatta plays out. So – in case you didn’t already know this, training will play a massive part in your success as a rower. I make no apologies for this being obvious, but in a field obsessed with marginal gains, this is a colossal one!

3 – Training consistency

However, a less considered element is an athlete’s ability to complete the training required. There are many athletes who have had the potential to develop their physiology to the necessary levels, but have failed to ‘survive’ the work required to fulfil it.

“Whoever invented the old adage ‘go hard or go home’ should probably go home and stay there”

Training smart is key to getting the most out of your physiology and being the fittest you can be. Those who do not necessarily have the optimal raw ingredients can trump those who do by methodically and consistently building their training base and fitness. Working too hard for three days then needing two days off to recover is considerably less effective at improving fitness than training sensibly for five days straight – even if it is within your capabilities. Temporarily over-reaching and allowing adequate recovery will ensure supercompensation. Whoever invented the old adage, ‘go hard or go home’ should probably go home and stay there.

4 – The environment

Finally, as we move out towards the edge of our model, one cannot underestimate the importance of our environment. While the majority of rowers are not training with elite crewmates in the best facilities, the most important element here is the culture we are part of.

The support we get – and give – from our club mates and crew, from team identity to communication and belonging, is crucial. These are often the things that draw people to the sport and keep them involved, whether they are trying to win or not.

Photo: Drew Smith