Earlier this year, while GB’s rowers were grinding out the miles on the water or the erg, Annabel Eyres was putting in almost as many hours in her studio. Having been chosen as one of six Olympian Artists for Paris 2024, her brief was produce a brand new collection of sport-inspired pieces, which will be exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris during the Games.

1992 Olympic athlete

Annabel competed at Barcelona 1992 in the Women’s double sculls, where she and Ali Gill finished fifth. (Notably, no British women’s crew finished higher than fifth at an Olympic games until Sydney 20001, and it was only at London 20212 that British women’s first won Olympic rowing gold medals2.)

Strangely, she probably woudn’t have learned to row at all had she not been a talented artist. She took up the sport to restore some discipline in her life after a socially indulgent first year while studying fine art at Oxford University. Annabel was soon completely hooked and went on to row the Blue Boat in 1987 and 1988.

In fact, Annabel’s artistic ability was key to enabling her international rowing career. Before National Lottery funding arrived in late 1997, GB rowers had to find their own ways to finance their training. Her solution was co-founding the rowing kit company Rock the Boat in 1989, and in 1992 she produced a range of t-shirts and sweats that raised around £10,000 for the whole GB Rowing Team. These fun, colourful designs, which she continued producing until 2019, after selling the business in 2004.

While sport and art clearly mixed so well for her, she was frustrated when she wasn’t taken seriously as an art student when she also spent a lot of time rowing. In the UK the pursuit of art and sport are seen as polar opposites,” she says, and contrasts this with the US mindset.

Art at the Olympic Games?

The short-lived era of the art medals

The ancient Greek games at Olympia – which inspired Baron Pierre de Coubertin to create the modern Olympic Games – encouraged the improvement of the ‘whole man’; mind as well as muscle. This was a philosophy that de Coubertin embraced too. Under his leadership the International Olympic Committee (IOC) introduced five art events for Stockholm 1912. These were painting, sculpture, architecture, literature and music.

From 35 competitors that year, the art programme grew to over 1,100 entries at Amsterdam 1928. But it then fell into decline, and the IOC discussed dropping this aspect of the Games. It was given a temporary respite on the basis that art was more universal than many of the sports being contested. In addition, many IOC members considered themselves to be highly cultured men who would not countenance a Games without art.

But practical reality didn’t match these ideals. Established artists sought to judge rather than compete. And questions about eligibility were raised about representations of non-Olympic sports such as cricket, rugby, fishing and even dancing. More fundamentally, many artists fell foul of the ‘amateurism’ rule that dominated the Olympic movement at the time. London 1948 was the last Olympic Games at which art medals were awarded.

The modern Cultural Olympiad

The concept of having a ‘Cultural Olympiad’ alongside the sporting Games has remained, though. In Paris 2024, the programme embraces a wide variety of community events. These include concerts, performances, exhibitions, dance shows, films, workshops for all ages, and celebratory parades.

As well as these mass-participation activities, an elite Olympic Artists programme was launched in 2018. Selection is in some ways tougher than for the sports themselves. Only a handful of artists are selected each year. To qualify, they must previously have competed as athletes at an Olympic or Paralympic Games.

Through the new Olympic-inspired artworks they are commissioned to produce, the Olympic Artists have a unique opportunity to share their experiences as both artists and athletes, and so to demonstrate the values at the heart of the Olympic concept.

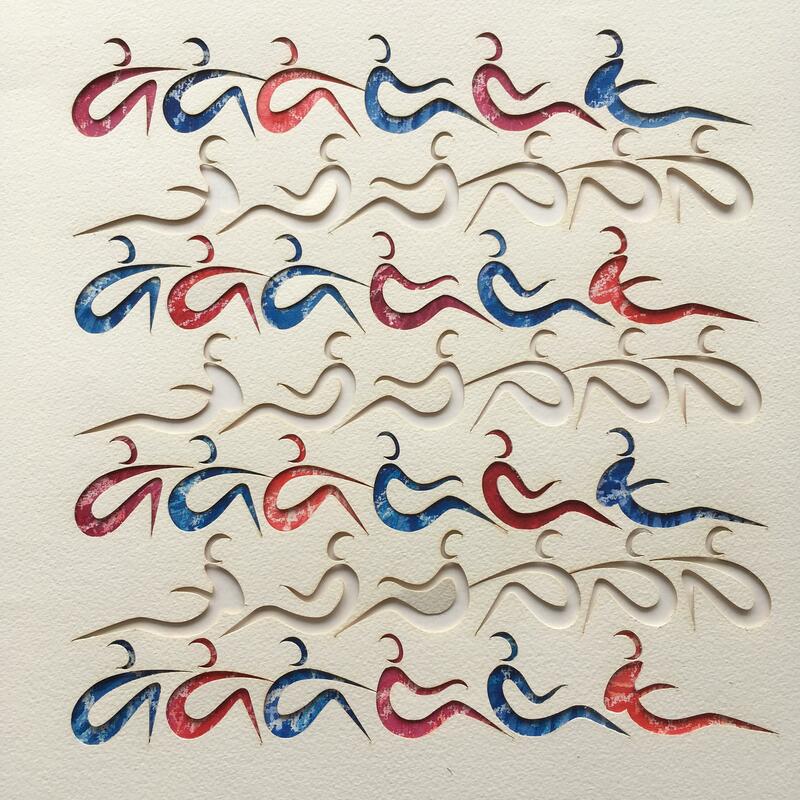

Annabel’s Olympic artworks

“As an artist I’ve always been drawn to the human body, its dynamism and range of movements,” Annabel explains. So each of her six pieces for Paris 2024 features a series of figures in various positions associated with a different sport. These are all presented through her hallmark mixed papercut and painting medium, although each composition has a unique style, reflecting that sport’s vibe. She has also produced two additional versions using wooden reliefs that are designed to be handled to embrace the concept of Braille, as used on the reverse of the Paris 2024 medals.

Rowing, with its repetitive range of movement through the stroke cycle, is perfect for this ‘series of figures’ approch. So it’s no surprise that the rowing piece is one of her favourites in the collection. Three of her other pieces feature equestrian sport, swimming and running. But she found surfing and breaking (break dancing) – both of which are new to the Olympic programme for 2024 – the hardest to capture, because of the freedom they involve.

“I was thrilled to be selected,” Annabel says. “From a personal point of view – because of my past as an international rower – it’s the most important commission of my life. And I never thought I’d be so involved in another Olympic Games, 32 years on from racing in Barcelona.” Her six pieces will be moved to the Olympic Museum in Lausanne after the Games. You can see more of her work at AnnabelEyres.com.

The Olympic Games motto is ‘Citius, Fortius, Altius’ – meaning ‘faster, stronger, higher’. But when it comes to the work of the Olympic Artists, the most appropriate description is ‘Formosius’ – meaning ‘more beautiful’.

1Miriam Batten, Gillian Lindsay, Katherine Grainger and Guin Batten won silver in the Women’s quadruple sculls.

2Helen Glover and Heather Stanning in the Women’s pairs, Katherine Grainger and Anna Watkins in the Women’s double sculls, and Sophie Hosking and Kat Copeland in the Lightweight women’s double sculls.