Seat racing is a good way of selecting crews if you have lots of options and a finite amount of time. A simple concept, it is difficult to do well, however. Get it wrong and you might find things are more complicated after your seat racing than they were before it. Martin Gough uncovers how it works, and the pros and cons.

Having taken part in plenty of seat racing myself as an athlete and coach, I spoke to Rhona MacCallum – the coach for junior women at Tideway Scullers School and the women’s sculling lead for the Great Britain Under 19 team – for some more insight.

I also asked for opinions on social media on this often-brutal method of crew selection.

“As a rower I loved it – my favourite sessions were the fury of racing for a place in a crew,” replied Jane, a former club rower who went on to coach juniors in both clubs and schools. She added, “As a coach it was fraught with stress. But I always felt it gave the rowers a sense of something important happening.”

Why seat race?

With lots of athletes or a limited amount of time to select crews, there are limited options available apart from seat racing. Using performance in small boats or on the ergo may not find the best movers of bigger boats.

Seat-racing allows a coach to find out which athletes and combinations – on the day in question at least – make the biggest difference to the speed of the boat.

“Single sculls will give you a picture of your best athletes, but it doesn’t give you an understanding of crew cohesion, so we need to do seat races for those,” Rhona says.

Nick, a former club rower turned junior coach puts it in lay terms: “It’s useful to unearth boat movers whose technique may appear more agricultural [but] can shift boats. “What looks the prettiest from the launch is not always effective. Equally, some [athletes with] smaller ergs often surprise in seat racing.”

How to organise seat racing

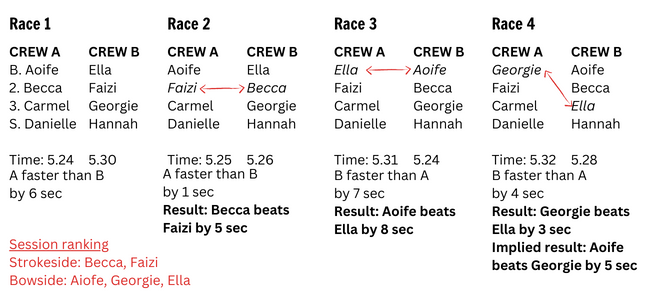

There are many different approaches but fundamentally, two boats complete a race then one rower from each crew swaps seats. A coach can observe the difference in result or time between the first and second race and attribute the difference to the swap.

Example

You need to run two races to get each piece of information, but the second race of one pairing can act as the first for the next. Race 3 might swap one of those already raced with another athlete, or two different athletes. As long as only one element changes per race, a comparison can be made.

You can also make inferences to give more results: if Athlete X beat Athlete Y by 5 seconds and Athlete X beat Athlete Z by 3 seconds then Z would beat Y by 2 seconds.

Who to test and how

To get that far, the first challenge is in deciding which athletes to test. Available time may limit the number of races that can take place, and therefore the number of athletes who can be compared. “The performance profile athletes put in through the year, through their ergs and their small boat performances, starts to build a picture,” says Rhona. “Ideally you know what seat races you need to do because of that picture, rather than having a free-for-all on one weekend in July.”

You need to decide whether you’ll race the crews side by side or in head-race style”

The next challenge is arranging the practicalities.

In general, coaches seem to prefer 1500m or 1250m seat races to gain reliable results for selecting crews to race 2km, without tiring athletes too quickly.

Still water and a straight course help to control potential variables, but you still need to decide whether you’ll race the crews side by side or in head-race style, which means they race without reference to the other.

Coxed seat racing

Using coxed boats may help eliminate steering inconsistencies, although it introduces another potential variable in the effect coxes have on different crew members. Fours, rather than eights, are likely to highlight differences more clearly.

Some race formats set rules for how much a cox can say – perhaps the same calls at certain points – but others (such as the GB U19 trials) use the process to select coxes too.

Matrices in seat racing

If athletes are of sufficient standard, a pairs or doubles matrix is probably the best place to start. A pairs matrix might include eight athletes, with each rower racing with each of the four from the other side. The doubles version allows everyone in the group to row with everyone else. Both methods produce an overall ranking, which will help inform seat racing in bigger boats.

Ratings in seat racing

Rate capping is likely to improve uniformity between races. GB U19 trials tend to set caps at 32 strokes per minute in spring and 34 in July.

“I will often rate-cap racing to ensure consistency,” says Rhona. “That stops everyone going out like the clappers in the first half of their first race.”

Detail is vital

How much information should athletes be given? How do you handle appeals or accidents, such as a crew clipping a buoy mid-race?

“I ask for the athletes to trust me and to trust the process,” Rhona says. “I will not give them a total number of races and I will ask them not to guess what’s going on. We’ll say they’ve got an indeterminate number of runs over several days and every piece of data counts.”

How big a margin is enough for a clear verdict?

Athlete appeals need to be known about before any swap is made. Then you can decide whether to re-run a race or make a timing adjustment, without influencing the next race.

How big a margin is enough for a clear verdict? One suggestion is that a second could be the margin of error for those using a manual stopwatch. Make that decision before starting.

Limitations of seat racing

Before seat racing begins, a coach should also decide how definitive the results will be. Are you happy for evidence gathered over the course of the year to be overturned by the result of a single race?

Club rower Matt recalls seat racing for a place in a Henley club crew: “I was in a fours matrix where I destroyed another rower after a swap. The coaches then decided it wasn’t representative so discounted it. It was the right decision – he was better than me on all counts – but begs question what was the point?”

“There are times when someone has… lost a particular seat race but the rest of the evidence shows you that seat race doesn’t quite work.”

With Tideway Scullers juniors, Rhona says: “Seat-racing is only part of the process. The risk is that it becomes a defined ranking for athletes. They assume that someone is ranked above someone else [forever]. So also I’m looking at constant data from training day-in, day-out.

“There are times when someone has made a boat go fastest. They’ve lost a particular seat race but the rest of the evidence shows you that seat race doesn’t quite work. I think it has to be part of a big tapestry of information you’re looking at.”

One challenge in a club environment might be finding eight athletes who will perform consistently through the process. One athlete tiring far more quickly than another can affect results for everybody.

Advice for an athlete entering seat racing

Going into a seat racing for the first time may be daunting for athlete, especially when the stakes are high.

Rhona’s advice is to see the whole process as an opportunity to learn more, rather than just as a selection method. “Part of the success we see each summer is because the trials process is competitive,” she says. “Often seat-racing in a trials context provides the best and closest racing that many athletes have had all year.”

Her advice for any athlete doing trials in small boats is: “Make sure you can steer. Make sure you’re confident sitting in different seats, and making the calls. And make sure you’re never doing those things for the first time in an environment where it matters.”

Finally, she says, don’t over-think it. “Usually, seat racing is most successful when people just get in a boat and try to make it go as fast as possible.”