In this second article of two, Alex Wolf from Science of Rowing, explains how to use ‘clarity of outcome’ to move your boat faster

In the previous article, I described ‘clarity of outcome’ as being the specific and targeted end goal we are hoping to change.

Because it is focused, it is explicit and specific. The less explicit we are, the more generic it becomes and the harder it is to create real and meaningful change.

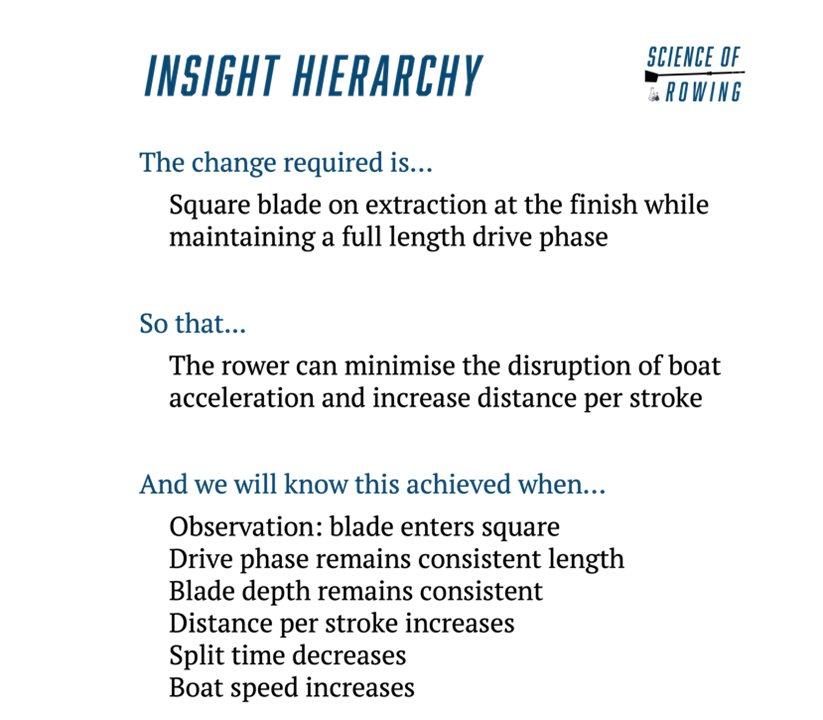

Clarity of outcome relies on the degree of insight we create around the area of change. The insight hierarchy shown in Figure 1 is an effective way to achieve the insight needed. It asks us to describe what change we want to create, the difference it will make, and how we will know if we have achieved this change. This is always the start point for establishing clarity our outcome.

Now that we have clarity of outcome, we need to know what to do with it!

One of the key points around clarity of outcome is that we should list all the areas around the rower/s we are working with that we would like to create change to improve performance. Remember, performance is the act of and not the level of competition. Each rower should have a list of areas which could potentially improve performance. It is important rowers are viewed individually so we can focus specifically on their needs. This process can also be used for crews to identify how that crew can improve performance too.

Prioritise the changes needed

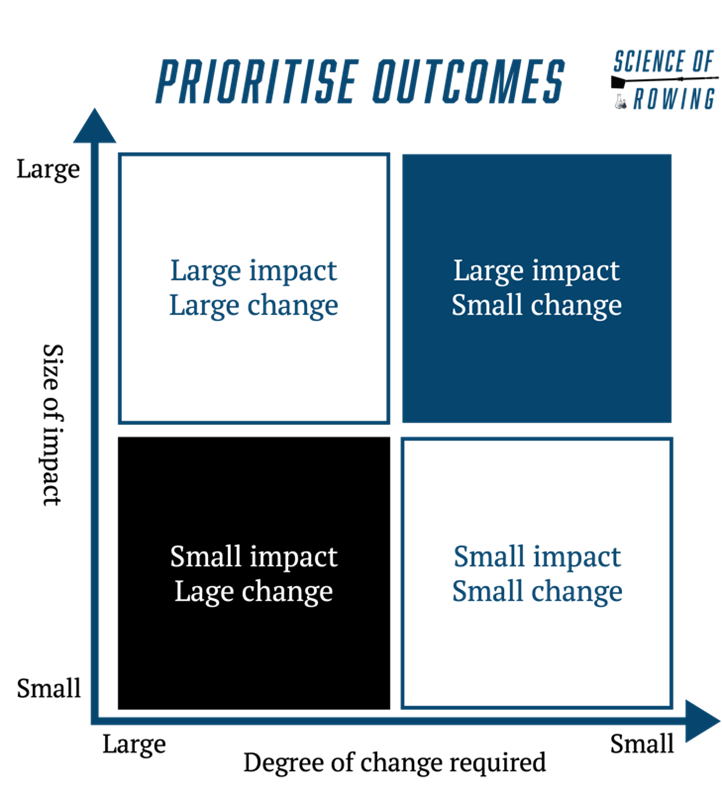

We must now prioritise each area based on the likely impact on the end performance. To determine this, we need to identify the impact these areas are likely to have on performance and how much change is need to for that impact to be observed.

Figure 2 below outlines how you can start to prioritise each area. The horizontal (x) axis shows the degree of change needed for the impact to be achieved, and the vertical (y) axis shows the size of the impact on performance.

You will notice that the degree of change on the x axis is inverse to the size of impact. As you move from left to right along the x axis, the degree of change moves from high to low. This produces four boxes. Anything in the blue box requires a small degree of change but has a large impact of the eventual performance. This could be described as ‘low hanging fruit’. Anything that is placed in here should be prioritised.

The ‘long-term projects’ in the top left and the ‘fillers’ in the bottom right come after this.

Any ‘tough nuts’ in the black box (requires a large degree of change and has a small impact) can be deprioritised.

Once outcomes have been achieved, the beauty of this method is it allows you to re-prioritise. This always allows you to focus on the rower in front on you and their specific needs.

Prioritisation not reductionism

People often challenge me on this as being a reductionist model. Reductionist models reduce performance down to the fewest constituent parts and very likely ignores everything else. In this model, we don’t reduce, we prioritise, then re-prioritise and have the opportunity to explore new areas rather than being relegated to ignore opportunities. It is important to note too, that we can focus on more than one outcome at a time but probably no more than two to three. Otherwise, we won’t have enough time within the training programme to make any meaningful change.

Use outcomes to select methods

By establishing and prioritising clarity of outcomes, we can now move to methods. Methods are the opposite side of the same coin. We can select a training type only once we have clarity of outcome. If we select training methods before establishing an outcome, we will lack clarity about the purpose of the training. There is a lack of focus and maybe even a lack of care around the intention and the athlete’s performance. It is the rower who becomes the victim in this situation. We must focus on the outcome first.

Clarity of outcome provides explicit focus on what we want to change. This helps us to be very clear around what we must change. This provides us details of the type of adaptations we need to focus on, whether that is a physiological or coordinative adaptation. We can then identify training methods that will create the required adaptations within the constraints in which we operate.

Understand your constraints

During this selection process, consider how the aggregation of training methods will result in the desired changes. For example, if an outcome is to increase central energy system/metabolic adaptations (crudely, heart and lungs), the traditional way of achieving this is to do a lot of steady state training. This may work well if your rowers have opportunities to do very large volumes of low-intensity training. However, rowers who can only complete 50-60km a week will not benefit in the same way as they simply won’t get enough distance in to create the required physiological adaptations. It’s tempting to take a high-performance training programme and simply reduce the volume, but we may fall well short of our intended outcome.

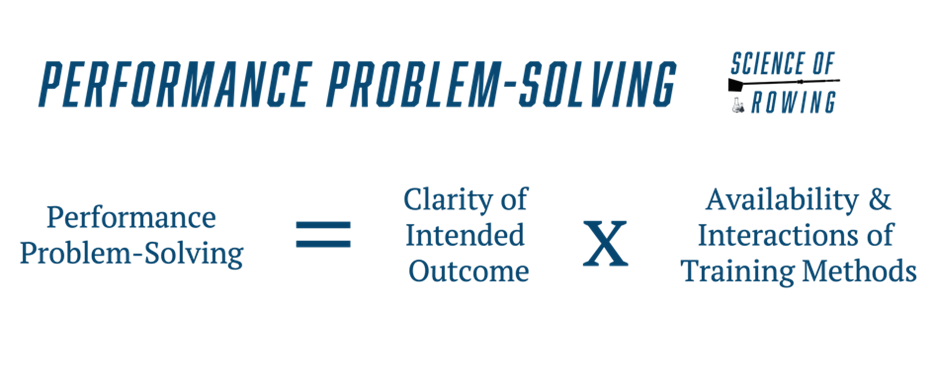

The movie Moneyball is about a baseball team manager’s attempts to put together a competitive line-up on a limited budget. In it, the manager is given some options on players who might help them emulate the successful Yankees. The manager replies, ‘If we play the Yankees in here, we will be beaten by the Yankees out there’, referring to pitch. This, I think sums up the methods part of clarity of outcome. We must be specific about what we want to change. And we must be explicit around how we can make that change based on the available methods to achieve this. This is how we describe performance problem-solving at the Strength and Conditioning Academy:

Conclusion

I hope that this two-part performance problem-solving article has shone a spotlight on the key tenets of performance (the act of and not the level) and how we, as coaches, have an opportunity to be more specific and targeted with our coaching practices.

Without clarity of outcome, we lose that opportunity to create meaningful change with the rowers we work with. Following the structures outlined within the article will certainly help you get closer to having clarity of outcome.

We also need to consider the most effective methods used to attain the changes we’ve identified based on the constraints that are present within our coaching practices. For me, constraints are not viewed negatively but as a positive stimulus to look at things differently. Constraints often result in creative and innovative practices (new and useful for the user) and allow us to optimise outcomes.

Part 1 suggested working through the insight hierarchy. If you have completed this for several the potential changes, try working through the outcome priorities outlined in figure 2. Draw an x-y axis with degree of change required on the x (horizontal) axis and the size of impact on performance on the y (vertical) axis. Place each outcome on the graph. You will then see which ones to prioritise based on how impactful and how much of a change is required. This can continuously be referred to when reprioritising outcomes.

British Rowing member offer

All British Rowing members can get to a 20% discount on Science of Rowing subscriptions. To get your code, just log in to the British Rowing Membership system, then go to Member Details>Member Benefits.