In this fourth article covering the different elements that make up elite rowing training programmes, GB Rowing Team Olympic High Performance Coach Dan Moore explores the value of strength training for rowing.

In the first three articles in this series, we’ve introduced a variety of concepts that athletes and coaches alike can use to drive physiological changes which, when stacked up, provide the main determinants of successful elite performance. These have primarily been focused on the endurance (or aerobic) nature of the sport because approximately 70-80% of the energy requirements in a 2,000m effort to come from aerobic energy pathways1. However, as rowing also has a large strength/power component, this article focuses on the use of strength training in elite rowing training and considerations when programming it.

Is strength training an essential part of all elite rowing programmes?

Reasons why strength training contributes to boat speed

Within the GB Rowing Team strength work is a mainstay of both the men’s and women’s training programme and approximately 20% of totally training time is allocated to it. This proportion, which neatly represents the anaerobic sections of a 2,000m race, is common in other elite rowing programmes too2,3.

Rowing is a leverage based sport in which athletes have to overcome the drag resistance that exponentially increases the faster a hull travels4. Therefore it’s not surprising that larger, longer-limbed athletes have tended to be more successful at the elite level5,6. More specifically, top rowers usually exhibit greater lean (fat-free) muscle mass and this is particularly true of male athletes5 because of the need for higher power to overcome the drag of athletes with greater mass. Due to these requirements, strength training can often be necessary to build the required muscle mass to generate hull speed.

Reasons not to include strength training in your programme

However, as mentioned in the first article in this series, there are arguments that strength training is not always necessary. One case is when an athlete is deemed already ‘strong enough’ for what is a mainly endurance sport. Of course, if the athlete has a background in a more power-based sport such as rugby or sprint, throw or jump athletics events then it is reasonable to assume they will be stronger than the average rower. This doesn’t mean they will necessarily have optimal strength in the key muscle groups rowing uses and therefore, with the aid of physio/S&C screening, they may still need to use adapted strength training to focus on rebalancing or robustness work. Also the specific strength they have gained in other sports may deteriorate as they cease training in them

Another opinion is that the act of rowing itself provides a resistance that muscles have to overcome and this can provide stimulus enough to maintain an appropriate level of strength8 (perhaps with the occasional addition of a bungee). This argument carries the assumption that to train effectively you merely have to complete the performance you’d produce when competing in your sport e.g. rowers row 2,000m flat out each day; long-jumpers repeatedly jump into a sand pit etc. whereas this is clearly not the case.

Another reason why strength training might not be the right thing for your programme is time. As explained in the concurrent training section below, athletes need to do two to four sessions per week of strength training to benefit from it if they’re also doing high endurance mileage. If your programme can’t accommodate that, other types of training are likely to be a better use of your time.

Conclusion: always know why your programme includes strength training, if it does

Coaches and athletes should always be clear what the intended outcome of each strength training session is within a training programme, whether it’s to increase overall strength or lean muscle mass, or conditioning and robustness.

How to programme strength training throughout the rowing season

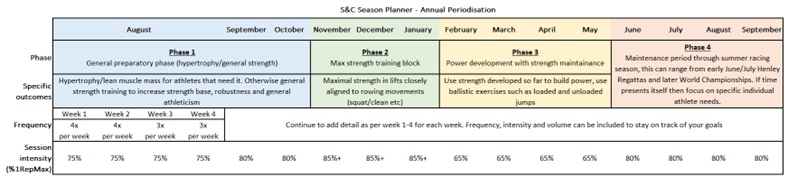

There are different potential outcomes from strength training, and these should be approached at different points of the season due to their specific demands. GB Rowing Team Strength and Conditioning coach Sam Boylett-Long explains that the traditional approach is to focus on hypertrophy (increasing muscle mass) and maximum strength during winter periods. This is for several reasons. First, you’re likely spend more of your training sessions off the water; second this type of work does take time to improve so it’s better to start as early in the season as possible; and finally, you need muscle mass and strength before you can produce power (force times speed).

In his article ‘Everything you want to know about resistance training’, Sam outlines a very helpful resistance training season planner, also shown in Figure 1 below. You can adjust this for your specific calendar when writing your training programme. His article also contains links to more detailed information about how to develop the specific areas of hypertrophy, strength and power training.

Sex differences in weight training

A final consideration with weight training is whether you are writing a programme for male or female athletes (or both). Various research studies have found that strength training is equally prevalent in elite rowing training for both sexes but often for different reasons. Due to the drag element of rowing, male rowers require proportionally higher force outputs than female rowers for the given boat speeds; and research has found successful male rowers have been differentiated by muscle girths where women have not7. Typically, female endurance athletes have a higher proportion of Type 1 (slow twitch fibres, which are aerobic) than men9.

This leads to two opposing questions: first, if women require less overall force in elite rowing, then should they do less strength training? But second, if they typically have lower relative muscle mass and fewer Type 2b (anaerobic) fibres, should they do more strength training?

There is, in theory, no absolute answer to this conundrum but in the GB Rowing Team weight training is deemed an important part of the programme for both male and female rowers at the same volume on both sides (20% total training time). Where it does differ however is that the women’s squad will continue strength training further into the racing season than the men’s programme to maintain muscle mass and strength which otherwise drops off faster in female athletes compared with males.

Concurrent training

One of the largest challenges in rowing training is simultaneously attempting to create both strength and endurance adaptations11. This inherent juxtaposition is called concurrent training and it is where many programmes struggle; athletes do a lot of training but tend to improve neither element.

The simplest message here is you can’t get away from the fact rowing requires both and it is best to commit yourself to this. Improving strength in an elite training programme (of 15-30 hours per week) is harder than you might expect because the endurance adaptations will suppress strength adaptations. Two to four sessions per week of strength training will be required to seek improvement. Simply rowing each day and adding a single weights session per week is unlikely to be enough to improve your maximum strength.

It is vital to appreciate the role that strength has in elite rowing. Nevertheless, this article has outlined the considerations you take before deciding whether to use strength training in your programme rather than assume it should or should not be used. Once you have decided what is right for you, do use the appropriate guides to understand more about the various types of strength and conditioning.

In the next article, I will be looking at the use of training camps and how you can use them effectively as part of your year plan.

References

- Maestu, J., Jurimae, J., & Jurimae, T. (2005). Monitoring of Performance and Training in Rowing. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 35(7), 597-617. 10.2165/00007256-200535070-00005

- Tran, J., Rice, A. J., Main, L. C., & Gastin, P. B. (2015). Profiling the Training Practices and Performance of Elite Rowers. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 10(5), 572-580. 10.1123/ijspp.2014-0295

- Treff, G., Winkert, K., Sareban, M., Steinacker, J. M., Becker, M., & Sperlich, B. (2017). Eleven-Week Preparation Involving Polarized Intensity Distribution Is Not Superior to Pyramidal Distribution in National Elite Rowers. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 515. 10.3389/fphys.2017.00515

- Di Prampero, P. E., Cortili, G., Celentano, F., & Cerretelli, P. (1971). Physiological aspects of rowing. Journal of Applied Physiology (1948), 31(6), 853-857. 10.1152/jappl.1971.31.6.853

- Winkert, K., Steinacker, J. M., Machus, K., Dreyhaupt, J., & Treff, G. (2019). Anthropometric profiles are associated with long-term career attainment in elite junior rowers: A retrospective analysis covering 23 years. European Journal of Sport Science, 19(2), 208-216. 10.1080/17461391.2018.1497089

- Edwards, A. M., Guy, J. H., & Hettinga, F. J. (2016). Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race: Performance, Pacing and Tactics Between 1890 and 2014. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 46(10), 1553-1562. 10.1007/s40279-016-0524-y

- Kerr, D. A., Ross, W. D., Norton, K., Hume, P., Kagawa, M., & Ackland, T. R. (2007). Olympic lightweight and open-class rowers possess distinctive physical and proportionality characteristics. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(1), 43-53. 10.1080/02640410600812179

- Lawton, T., Cronin, J., & McGuigan, M. (2013). Does On-Water Resisted Rowing Increase or Maintain Lower-Body Strength? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 27(7), 1958-1963. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3182736acb

- Hunter, S. K. (2014). Sex differences in human fatigability: mechanisms and insight to physiological responses. Acta Physiologica, 210(4), 768-789. 10.1111/apha.12234

- Lawton, T. W., Cronin, J. B., & McGuigan, M. R. (2012). Strength Testing and Training of Rowers. Sports Medicine (Auckland), 41(5), 413-432. 10.2165/11588540-000000000-00000

Photos: Dianna Bonner.