Coach consultant Robin Williams explores the impact that length has on the rest of your stroke, suggesting tips and drills to help you perfect your technique.

A crew which can generate more length, more power and more strokes per minute than the opposition, should win the race, at least in theory. But there’s more to it than that because this bald statement assumes some things which in reality may not hold true.

For instance, can you have too much length? Yes, you can. Can you apply power incorrectly? Yes, of course; and can too much rate be a bad thing? Once again, yes it can, especially if it sacrifices rhythm. This month I want to look in particular at length and power and the question of rate will get attention as a result.

Length

Length is obviously important. You don’t win many races with short strokes, so start by having an overall target in mind. What does “long” mean to your crew? Then you’ve got to see if you can handle the length; in other words, apply your power to that arc taking into account your height, power, flexibility etc. If you try to row too long, it will be impossible to generate power well.

Sweep boats normally aim for a total arc of about 85-90 degrees, with a catch angle of 55 and finish of 32-35. Tall rowers might row 95 overall with 60 at the catch, while shorter, less flexible, or less physical crews might be nearer 50 at the catch. Scullers generally sit in a range of 110-115 for tall seniors and 100-110 for shorter ones, with catch and finish angles around 60-65 and 45-50 degrees respectively. If the total arc for sculling is under 100 degrees, then most coaches will look at narrowing the span and shortening the oars, but we are entering the dark art of rigging with this conversation, and I really want to focus on the technique of length!

Whatever the theoretical numbers and geometry of the rig, the length has to feel right in real life, and work at all stroke rates. The human body is good at self-gearing and adjusting to the boat set-up. So, the next step is to look at your geometry and see if your own angles can support the arc you have chosen for the oar. It is easier to row long at low rates because movements and forces are controllable, but people often struggle at higher tempos.

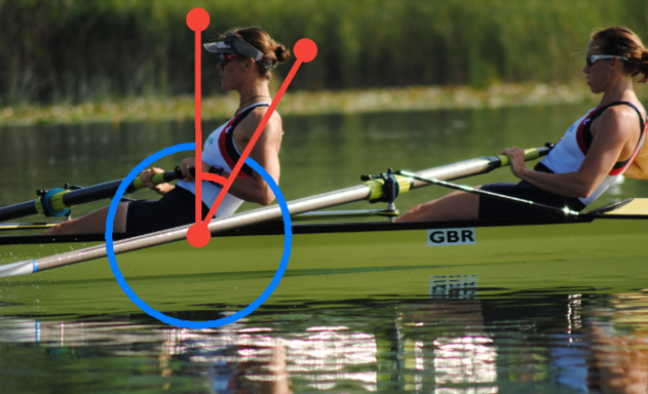

The trunk angle is an important influence: how much forward reach, how much sit-back at the finish?

Posture matters too, because poor bracing low down will dissipate the leg power before it even gets to the oar. So, the trunk is a potential limiting factor. A typical forward angle is around 55-65 degrees – see picture above. It is obvious to the naked eye or from video that this angle looks about right. There’s a good possibility that when the rower pushes hard, the trunk will support and engage that pressure without deforming. Conversely, too vertical will allow the body to open too early against the legs and too flat means the trunk is weak and usually there is some seat slippage or ‘bum-shove’.

“Getting the combination right between length, power, and rate needs to start with rig and set-up”

This is all pretty obvious stuff. Except that when you are the one doing the rowing it is actually quite hard to judge length and your effective range, so even if you know the facts you still have to know whether you are doing it right. Those clubs which have telemetry systems to measure angles and forces will know that from an actual sweep arc of 90 degrees, the catch can easily lose 10 degrees by the time the spoon is entered and engaged, and at the finish you can lose another 5-10 by not holding the pressure properly. More proficient rowers will be doing well if they can reduce wasted degrees to under 10 in total and keep their effective arc (sweep) in the 80s, but plenty of us lose 20 or more out of our precious 90-degree arc.

Things to avoid

- Spoon: squaring late, sky-ing, going deep, going shallow

- Shoulders: over-reaching at the entry, dipping, stiffening up

- Posture: lower back slumping, or tucking under at full slide

- Kinetic chain: the legs push, but the pressure does not connect to through to the handle

- Kinetic chain: rower uses the wrong movement to initiate the stroke (eg arms)

- Timing: pushing off before the spoon has fully entered the water.

“Many of us will remember the highly successful Canadian men’s eights from the early 2000s which used a huge lean back!”

How to get it right

Try to generate length from the upper body first, and the legs second. From the finish to about one-third slide get the arms out long, shoulders relaxed, knees unlocked and set the trunk angle forward as described earlier with the chest in front of the hips. The rest of the stroke length comes from the wheels because the slide will transport the upper body and handle as it goes. Rowers often do this part quite well, but ruin it by going for something extra at full slide. This upsets the timing and synchronisation of the entry/catch and adds weight to the stern.

With the handle well organised across your shins there is room to square it and rise to the water as your wheels arrive – see image below. The feeling you want is one of balance over the stern, not tipping, dipping, or heaviness. So, nearing full slide try to keep lightness and control on the stretcher, and stay tall and balanced in the trunk and chest.

Useful drills are:

- One-third slide pauses: to set the position.

- Legs only air strokes with rate lifts: to practise control of forward momentum.

- Legs only rowing off the front: to practise arriving, entering, and loading through the legs.

Length at the finish is obviously important too.

Typical lean back angles at the end of the stroke will be around 25-30 degrees from vertical – see picture above. This again has some caveats. Shorter athletes will need more lean-back than taller ones to achieve the correct arc.

In faster boats like the eight and quad scull there is a little less emphasis on the finish body angle than in the slower ones like the single because the load is disappearing faster than in the slower boats. The important feeling here is not to lose contact with the foot pressure and ‘go off the back of the seat’. So long as there is outward pressure to the stretcher and incoming pressure on the handle then the finish feels supported. Once you lose one of those pressure points the stroke effectively is over and further length is redundant.

Over-exaggerating the lean back ploughs the bows into the water and can cause the hips and elbows to slump. However, many of us will remember the highly successful Canadian men’s eights from the early 2000s which used a huge lean back! It just goes to show that you can make different things work in rowing. That brings us on to power and how it works with length.

Power and length

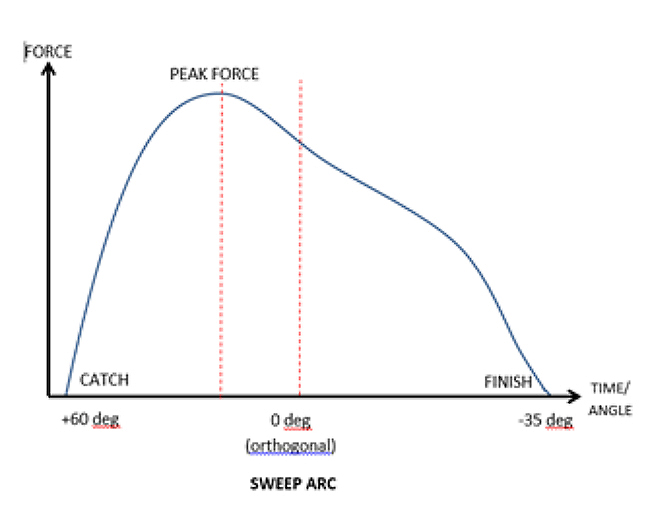

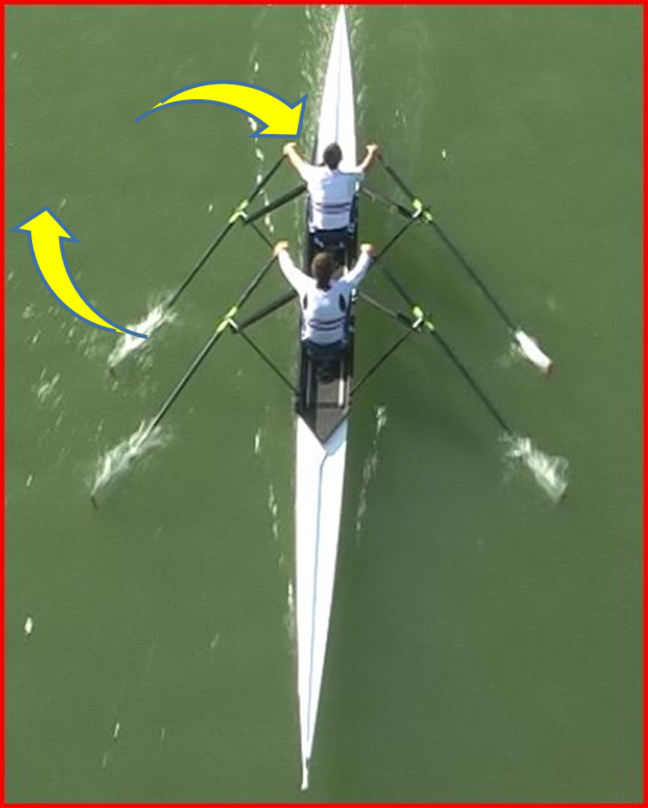

Looking at the generic force/time curve example you can see the peak is about a third of the way through the drive. If the rower ‘hits’ the front of the stroke it tends to block or freeze the load: it’s too much force against an inefficient angle and an aerial view of the catch shows how this might happen – see picture below. A force can be applied against a concrete wall but the wall won’t move! Hitting the catch is just like that.

So, with peak force on the oar at about 15-20 degrees before the orthogonal, it comes about a third of the way through the leg drive. The heels come down, the knee angle opens to beyond 90-100 degrees, and the trunk is just beginning to open at the hips.

To develop power that means some movement has to occur. Movement uses angle and angle uses time, so the power needs to be applied progressively against the arc. It is a matter of working with the boat not over-forcing it.

From catch to peak force certainly needs some effort – a strong squeeze- but also patience. As the curve peaks, the feeling in the boat is that the load is giving way and rewarding you with willing movement, acceleration and ‘send’. It is now quite easy to imagine that when rowing the right length, you can also generate a dynamic and powerful stroke and, in so doing, it won’t be a problem to achieve race rates. It is largely a matter of getting the two phases of loading and accelerating right.

Drills for loading

- Rowing with half crew: the dead weight makes the load more obvious, plus there is time to set the spoon and find your leverage point.

- Outside-hand down-handle: creates a small over-load so you appreciate the muscle chain connection and avoid any ripping at the beginning.

- Bungee under boat: gives a close-to-normal feel, but assists timing and loading at the catch. Very good for training your lower trunk area.

- Build down from front stops: ie legs only, legs and trunk, legs, trunk and arms. This is helpful because it develops feel for the load phase transitioning to acceleration.

Drills for power

- Rate builds from back stops: good because quarter slide, half, three-quarters all allow you to develop power and acceleration because the loading angle is easier.

- Short-slide rowing: a shorter slide means less load, so the remaining leg drive and trunk opening will be more dynamic.

- Power strokes: low rate, full length, full power. Obvious feel for both load and acceleration.

- Starts: these are great, not just to practise starts per se, but because the loads change a lot over the first 10 strokes you can experiment with the length versus power recipe.

- Try 15 x [17 firm strokes/5 light]: done at rates 30-36; each set of 17 needs some build-up strokes of speed and rate, then to hold rhythm before winding down for 5 and allowing the speed to drop back.

Conclusions

Getting the combination right between length, power, and rate needs to start with rig and set-up.

Then look at your own geometry and decide your working angles – leg compression, trunk extension, and how far to sit back at the finish. Finally, the individuals have to find a happy compromise so that the crew can all row together. I had personal experience of this many years ago rowing as a 5’10” lightweight in a heavyweight GB eight behind a rower who was 6’8” tall! The key thing was to make sure that the two basic phases of the drive were together – loading and accelerating. If I had over-reached, I would still have been loading when he was accelerating, which would not have worked. Matching the phases worked fine, even if the exact angles were slightly different.

Finally, a good tip is to watch the stern: if it is dipping or slowing at the front then it will pay to check your length, and also whether you are making any extra, un-necessary movements.

Photos courtesy of Robin Williams