With Black History Month running throughout October, we celebrate a few of the black rowers who have made their mark. Thanks to Tim Koch of Hear the Boat Sing for kindly allowing us to republish an edited version of their article below

Black History Month 2021 spotlights the achievements of the black community, celebrating the past but it also looks forward to the future, embracing the opportunities that lie ahead by creating a sport that is truly welcoming and open to everyone.

Back in June last year, Tim Koch of Hear the Boat Sing wrote the article below spotlighting the career highlights of trailblazers Frenchy Johnson, Aquil Abdullah and Anita DeFrantz.

A look at ‘a few of the few’ black rowers perhaps illustrates how much poorer the sport must be through the loss of all those excluded by intentional and unintentional prejudice, and, by implication, how much poorer prejudice makes life in general.

Clearly, historical reports will contain words, attitudes and images that are now considered offensive.

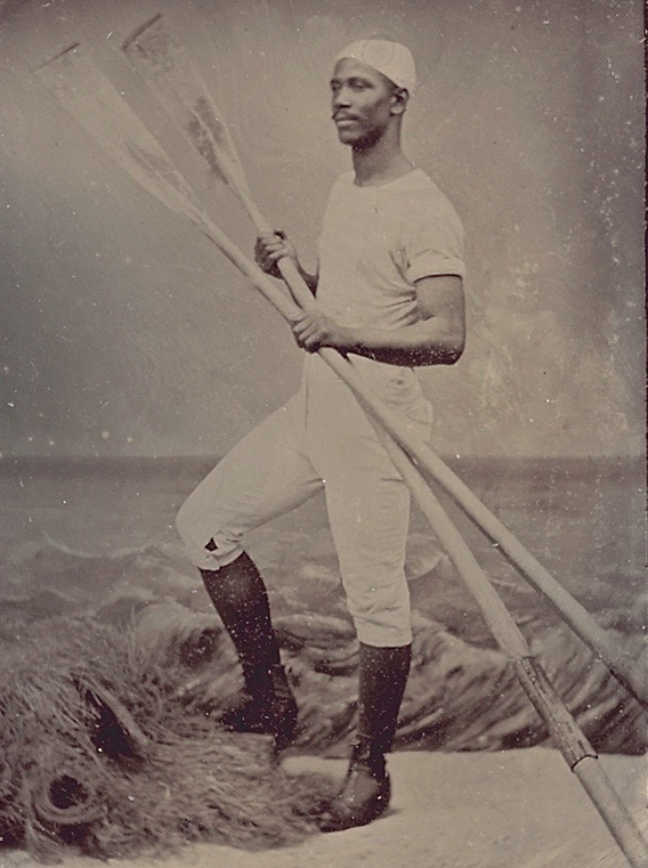

Describing Frenchy Johnson in a tantalising footnote in his thesis of 2000, A Social and Technical History of Rowing in England and the United States, Stewart Stokes wrote:

Frenchy Johnson is a fascinating character on whom very little information (is) available. He was a black man who had learned to row in the deep South at some point, likely in the slave races which were popular among plantation owners during the period when rowing was exploding in popularity around the country.

We do have a form of obituary for Johnson from the New York Clipper of 24 March 1883 but, unfortunately, there is little personal detail. However, it begins:

The death in Florida of Frenchy A. Johnson, the well-known colored sculler and trap shot, is announced in a dispatch dated March 19. He was an excellent second-class oarsman, and was repeatedly successful in regattas and match races.

The Clipper gives accounts of many of Johnson’s races, beginning in June 1877 and ending with possibly his last race in July 1880. He did not win any of the first four three-mile races described, but he was either second or third to some of the best-known professional scullers of the time.

Things changed on 30 May 1878 at Silver Lake, Massachusetts, when Johnson unexpectedly beat the favourite and won a three-mile race with a turn in 21 minutes 36 seconds. He won again on 4 July at Boston and on 15 August at Silver Lake. In 1879, a couple of second places were recorded, one to probably the best sculler of the day, Charles Courtney.

In one of his last races, on 4 July 1880 in Boston, Johnson won in the double scull with ‘F. Hilley’. I assume Hilley was white and I imagine that such displays of teamwork between the races would have been rare at the time.

However, looking at the reports of Johnson’s races, it is interesting to see that he was usually written about with much the same respect given to the white scullers, this at a time when both ‘casual’ and overt racism would be normal in almost any reference to a black man.

Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of Johnson’s career in sculling was that he was, for a short time, the trainer to the very successful Charles Courtney. While Stewart Stokes says that how this happened is unclear, it is certain that during a famous and controversial race held between Courtney and the great Canadian sculler, Ned Hanlan, on Chautauqua Lake, New York, on 16 October 1879, Johnson was casually referred to in press reports as Courtney’s trainer.

The New York Clipper obituary concludes ‘After (July 1880) the deceased did little rowing, paying more attention to (clay) pigeon and glass ball shooting, at which he became an expert’. He died in Florida, ‘having gone there in search of the health he had lost’.

Olympic medallist Anita DeFrantz became the first American woman and first African American woman to serve on the International Olympic Committee (IOC). An advocate for all athletes, she was named by Newsweek as one of the ‘150 Women Who Shake the World’ and by Sports Illustrated as the ‘101 Most Influential Minorities in Sports’.

The publishers of DeFrantz’s autobiography My Olympic Life semi-summarise her life in typical book jacket style and conclude:

Her story is more than a civil rights and sporting victory for one person. It reveals how with grit and passion, one person can change the game positively for all.

After the 1976 Olympics, DeFrantz became a member of the US Olympic Committee (USOC) and practised at a public interest law firm but, in 1979, left to train for the 1980 Moscow Olympics. However, following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the US boycotted the Games. In response, DeFrantz filed an ultimately unsuccessful lawsuit against the US Congress stating that it was an athlete’s choice to compete or not. Despite the unpopularity of this challenge, she was soon working for the USOC, starting with the 1984 Olympic Organising Committee.

In 1986, DeFrantz was chosen to represent the United States on the International Olympic Committee (IOC). In 1997, she was elected as the IOC’s first female Vice-President.

Serving on numerous committees and boards with the IOC, the United States Olympic Committee (USOC), and many other associations, DeFrantz has championed the rights of athletes, women and people of colour. In particular, she is credited with the acceptance of women’s soccer and softball into the Games. The IOC’s summary of DeFrantz’s many appointments, achievements and honours is on their website.

In 2001, with the endorsement of the USOC, DeFrantz had sought to become the President of the International Olympic Committee, but, in some typically opaque IOC manoeuvrings, was eliminated in the first round of voting. Possibly she was considered too interested in sport and too keen on fair play to be in charge of the business that is the Olympic Games.

Back in March, Rosie Mayglothling conversed with DeFrantz in celebration of International Women’s Day for British Rowing and you can read the full interview here.

Aquil Abdullah was the first African American male to qualify for rowing at the Olympics. He was also the first African American rower to win the Diamond Sculls at Henley Royal Regatta in 2000. You can read more about him here.

Abdullah began sculling because he was an American football player who needed a spring sport his senior year of high school and he did not want to run ‘track’. Fortunately, he attended the only public/state school in Washington DC with a rowing programme and he decided to try it out.

Within a few months he was offered a scholarship to row at George Washington University. In 1996, he graduated with a physics degree and also became the first African American to achieve an American national championship rowing title when he won the men’s single sculls at that year’s US Nationals. He repeated the win in 2002.

In 2000, Abdullah missed qualifying for the Sydney Olympic Games by a third of a second, but after his Henley win, he was paired with Henry Nuzum and they began competing in the double sculls.

From 2001 to 2004, the double went to three World Cups and two World Championships and in 2004 it qualified for the Athens Games, making Abdullah the first black American male to row in the Olympics (two African American women had preceded him). The double finished sixth.

In 2001, Abdullah wrote a thoughtful book, Perfect Balance, in which he questioned where he belonged: in the predominantly white world of the sport that he loved or among other African Americans, most of whom knew little about it?

After Athens, Abdullah retired from the sport aged 31 but, at his home in Boston, he worked with ‘Mandela Crew’, an organisation that gives minority groups opportunities to row. The National Rowing Foundation (a non-profit organisation dedicated to raising funds to support the US National Rowing Teams) announced in June 2020 that he would be one of three new members of their board.

Despite having Washington DC, as his birthplace, being a member of the US Rowing Team and worshipping as a Roman Catholic, Abdullah encountered extreme difficulty in travelling following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in September 2001 and the hasty passing of the so-called Patriot Act.

Were the tall, handsome athlete white, Abdullah would have been considered ‘an all-American boy’ but racial profiling made him a terrorist suspect. Anyone guilty of having a ‘Muslim surname’ would automatically be taken aside at airports for long, in-depth questioning, no matter how many times they had previously been checked.

It once took Abdullah 24-hours to get from Princeton to Seattle and it was suggested that he could have made the trip quicker by rowing.

The journey of people of colour is indeed a slow one.

Normally these articles are only available to British Rowing members but we’re opening them to everyone in celebration of Black History Month 2021.

Find out how you can become a British Rowing member here.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–