Why do some people grasp technique quicker than others? And how can you ensure that you are one of the fast learners? Coach consultant Robin Williams outlines eight areas that might help

Some people pick up technique quite quickly while others take a lot longer. I have always been fascinated by this and what it is that makes it so – is it the person, the environment, or the coach, or perhaps a fortunate coincidence when all three come together?

Something definitely true is that whatever we learn only becomes real when it is fully internalised, that is to say when you feel it is your own idea, as if you had the original thought yourself. Then it is powerful and you have a proper understanding and belief that it is the right way – the proverbial ‘light-bulb moment’ when it suddenly makes sense.

So, how do you make that light bulb come on? How can you progress at the best rate for you?

There’s no doubt that basic environment helps if you are in a club which is well organised, efficient, with energetic and enthusiastic people, and goals to aim for. But everyone in the club would have that benefit and yet some would still progress faster than others. Good coaching will also help, but, in theory, everyone also has access to that resource too, so it boils down to what you personally do with these opportunities whether in a school, club, university or a national training centre like Caversham.

If my goal is to improve one thing per week it doesn’t take long before I’ve made a lot of useful advances. But do it now!

Below are eight key areas to work on.

1 – Attitude

A bit of simple preparation before sessions helps. Many rowers just turn up and see what is on the schedule for today. Be on time, be ready for the session and think what you can add to the boat, not just what you can get from it. Don’t just follow the programme, read it like you wrote it yourself and try to understand each session and how it links with others over time.

Think about change: if my goal is to improve one thing per week it doesn’t take long before I’ve made a lot of useful advances. But do it NOW!

2 – Curiosity

Look for ways to help yourself by asking questions of the coach and other better athletes. People like being asked their opinions – it’s flattering – and usually they like helping others. So, ask about the technical focus for the session, a specific skill you are trying to master, about drills you can try, things you can do out of the boat on your own.

In lockdown some GB athletes, for instance, organised webinars with retired medallists to see if there were any shared learnings which could help them.

Coaches used to say to me: “Exaggerate a change massively and maybe I’ll spot something different!”

3 – Risk

Don’t be scared of getting it wrong. You need to know what doesn’t work to figure out the right way and why right is better. Be prepared to go out of your comfort zone and explore. Right and wrong is just a scale. Coaches used to say to me: “Exaggerate a change massively and maybe I’ll spot something different!”

4 – Opinion

People are sometimes shy about giving their opinion in the boat for fear of looking foolish. Even coxes, who can see the oars and feel the hull are often reluctant to say things because they are unsure of the cure. But if the boat is sluggish or blade-work poor then say so, because agreeing on the problem is half the way to finding the solution.

Top rowers have an opinion about why each movement in the stroke happens and how the boat should feel, but are also humble enough to admit they can be improved.

You are looking for one stroke. One stroke which feels right, and then repeat it

5 – Logic

Rowing is common sense so if the boat is heavy, for instance, there will be a reason. If people are out of sync then strip it back to a simpler stroke by doing some pauses and establish better reference points at the finish, quarter slide or wherever, but try to find the point of error.

6 – Diligence

You are looking for one stroke. One stroke which feels right, and then repeat it. If you lose it don’t despair, just try to be consistent and find the good ones. Perhaps this is one reason why many teams see the single scull and coxless pairs as such useful training vehicles where experimentation is easy and feedback from correct or incorrect technique is very direct.

The fast learners tend to be tuned into their own bodies but they’re also aware of the external factors which might affect their stroke

7 – Learning processes

Armed with this mindset it now pays to think about the basic learning process we all face. With this knowledge we can understand why something seems easy or hard.

The learning model says you go through three stages of learning – cognitive, associative and autonomous.

Cognitive just means that initially you have to think, hard, about even a simple action because it is unfamiliar to you. Think about learning to drive a car. Then you start to see the association between two or more actions, like a good entry allowing you to make a good catch, for instance. Finally, your body can perform whole sequences of movements confidently and automatically because you understand the individual movement and its relationship to the whole.

Unfortunately, it isn’t a one-way process otherwise we would all become brilliant and remain so. If you change rate or pressure this might make the stroke feel less automatic and suddenly more cognitive.

Switching seat positions, boat type, a change in wind direction and a hundred other small things means our brains flit between these stages all the time. This is partly what feel is – the ability to absorb change and micro-adjust accordingly to keep the whole entity cohesive. It is a filtering system to remove or reduce disruptive influences. Sometimes it is instinctive and at other times it needs a cognitive decision.

But this is okay; rowing is an outdoor sport so things are not going to be 100% perfect and the better your skill set, the better you can cope instinctively.

The fast learners tend to be tuned into their own bodies in terms of balance, position, relaxation, readiness, but they’re also aware of the external factors like other people’s movements, the boat, wind, steering and things which might affect their stroke.

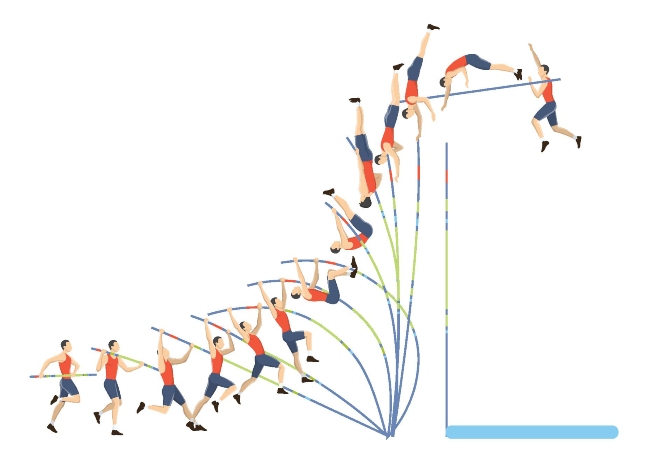

A pole vaulter runs along with the pole in the air like the rower carries the oar off the water

Drills like eyes shut, feet out, square blades, balance strokes and speed work can help, and rowing in different positions and with different people in the boat can also give useful perspectives.

Nick Clarry, who represented Cambridge in the 1992 Boat Race, rowed two events at Henley Royal Regatta in the same year and won both the Goblets and the Britannia on the same day, racing on different sides. Impressive!

8 – Useful concepts, themes and imagery

True self-help learning is tested when you have no coach at all or external feedback.

Can you still improve? Well, if you had some clear concepts to follow and you thought diligently about what they mean then you could get a certain way on your own.

Here’s a few areas, and I’ve expanded on three of these below.

- Leverage

- Rhythm

- Time

- Progressive power

- Let the boat glide

- Momentum and braking

Leverage >>>

This is a key one. What is the most common problem with rowers at the front end? The answer is mistiming.

The correct sequence is Arrive and enter… then Push but so many of us Arrive… Push and enter. The premature push/late entry means the spoon scoops or rips the water rather than levering the boat. I have never done a pole vault in my life, but use this as an analogy when coaching because it’s easy to appreciate, is amusing and makes a valid point: a pole vaulter runs along with the pole in the air like the rower carries the oar off the water. As he arrives at the jump, he drops the point in its socket and pushes off to create his point of leverage there. If he doesn’t do that, there is no possibility of achieving take-off – he will just keep on running!

No jump without putting the pole down, no stroke without entering the water!

But, as mentioned, very many rowers change direction before entering the blade. Fair enough, we are facing backwards, and the entry is out of sight, but there is no logic in pushing against thin air.

Rhythm >>>

An analogy to help explain this concept might be a kid’s yo-yo and the way you throw it away with a smooth, progressive force and let it wind itself back to your palm, returning your energy.

The image of pushing someone on a swing is similar – at full height the swing is slower and heavier, like the beginning of the rowing stroke, and you load, drive and accelerate it away using your large muscles and, finally, it leaves your fingertips. There is a rest interval before it begins its return arc towards the turnaround (catch) point again.

This imagery has worked extremely well with both novices and Olympians and has generated light-bulb moments more than once because instead of trying to fix a point of detail in isolation the rower can suddenly see the bigger picture, and grasps the overall sense of the stroke.

Progressive power >>>

The rowing movement sequences are very like a squat jump off the ground beginning with a squeeze from the toes, recruiting the larger quad muscles as you rise, then hips, back extensors, trunk opening and, lastly, the arms fly up. The dynamics and rhythm of it are similar too.

So, you would not collapse into the gym floor on the downward part, for instance. It needs to be an elastic movement if you want to connect several jumps in a fluid sequence.

These sorts of images can be useful because they establish the right thinking and that’s half the battle with technique.

Finding examples outside of rowing which are already familiar to you is a way to shorten the learning time and, coupled with a good attitude, curiosity, logic and a sense of urgency you might just get your own light-bulb moment.

Photos: Drew Smith and Shutterstock