Setting technical goals for the year will make progress more measurable, writes Olympic coach Robin Williams.

When it comes to planning your technical programme, we all understand the need for a year-round work programme which builds up endurance, strength, power and so on – yet often we seem to just deal with technique day by day. But you can plan technical improvement and, by thinking about when to work on certain skills through the year, you can methodically drive them higher. This is especially true if you are part of a group.

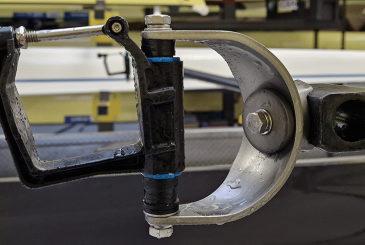

One of the great things about rowing is that it involves pretty much all of your muscles. You have to be fit everywhere and you need a good kinetic chain in order for your muscles to deliver the available power. From your toes through to your legs, trunk, arms, down to your fingers – one weak link and the whole power train is diminished. It all needs to be physically strong and technically robust.

“Poor organisation and sequencing is the most common mistake I see.”

I usually describe technique under two headings: mechanics and feel. Mechanics deals with the kinetic chain, the sequences of movement, your stroke arc, the forces – in fact all the measurable bits. As you translate these to higher pressures and rates there’s less time for thinking and more more need for feel. It’s helpful to know which you are going to work on otherwise the crew can have different expectations of a session.

So a technical programme will recognise the progression from mechanics to feel. For instance, you might decide that in October your crew will be able to do single strokes to a quarter, half and three-quarters of the slide in order to promote good preparation for the stroke, balance, slide control and togetherness. This might be at low pressure, low rate and even with some of the crew just sitting in the boat.

By November you might do these drills with the whole crew rowing and feet out, square blades, even eyes shut to increase the difficulty. By December you might aim to do this in a more complicated high speed drill – for example a quarter, half, three-quarters, full, three-quarters, half, quarter stroke pyramids done continuously and with pressure.

TIP

Set the technical goal: write it into your training session, set a time frame to improve it (maybe a week), grade it now and at the end (e.g. 7/10), then set another goal – but remember that you’ll be re-visiting this first one later on to make it 10/10!

When periodising (planning) your technique it can easily complement the work programme. Typically, your aerobic foundations are laid in early winter (October-December), developed with power in late winter (January-March) and honed in pre-race and race season (April-August). Technically, you can follow a similar progression. A simple example might look something like this:

Oct-Dec

Broad aims – at the low rates work on: long stroke, balance, slide control, clear sequences of movement, blade height, square finishes, and build strength in the kinetic chain, especially the lower trunk.

Specific drills – single strokes, pauses, legs only, legs and trunk, rock over exercises, inside/outside hand work, resistance work (bungee around boat).

Jan-Mar

Broad aims – sustain technique in tough sessions when fatigued; use longer pieces and higher rates to practise control of body mass and oar, maintain rhythm/ratio.

Specific drills – a quarter slide with square blades at medium rates, inside arm moving to firm with both hands; eyes shut rowing, power strokes with / without bungee.

You could then schedule further aims as you go into competition: starts with square blades, high speed hand drills, bursts, and so on. So you can see that it is quite easy to make a basic schedule and you can add detailed individual sessions from this overview.

The mechanics of the stroke

The mechanics – the sequences and the cognitive learning – are the foundations for your high skill racing stroke later on.

Everyone knows the traditional hands-body-slide recovery sequence and legs-body-arms in the power phase. It’s basic and it works yet poor organisation and sequencing is the most common mistake I see. As soon as people go up in rate a bit they sacrifice accuracy – the seat starts to move before they’ve properly cleared their hands which often means the trunk is not rocked forward. Without their weight forward enough they lack control on the slide and are still organising shoulders and oar handle at the front. This can add negative force on the stern and slow you down.

“The crucial aim is to clear your hands beyond your knees”

In my view YOU do the first stage of the recovery (hands and trunk), the BOAT does the second. The crucial aim is to clear your hands beyond your knees – this guarantees that the weight of your trunk is set forwards before you slide. You then sit still, in position, and the boat run slides your legs up to your chest bringing you to the entry nicely balanced, controlled, relaxed and able to enter, change direction and engage pressure instantly.

The power phase is the reverse – your feet quickly lock the spoon against the water (like a ‘pulse’ of pressure). This ‘catch’ is purely about attaching you to the existing boat speed and only then can you really move the hull with the legs and back. So the sequence goes, feet, legs, back, arms – it’s simple to say and harder to do but there are ways of practising it.

TIP

Try squat jumps in the gym; most people naturally do the correct sequence starting off from the feet, then into the quads, extending the back, etc. Rowing is similar but in a sitting position and with a load in your hands.

A stroke sequence is a bit like a 400m oval running track; if you get left behind you have to cut a corner to catch up. So it takes lots of practice to catch, drive, open, and finish together and then stay in sync through the recovery too.

This article was first published in Rowing & Regatta magazine in August 2010. Download the original article as a pdf.