This article is the second in a series by British Rowing Performance Satellite Coach Ben Reed on Monitoring and Assessment for Club Coaches. It’s based on a presentation he gave at the 2025 British Rowing Coaching Conference along with former British Rowing Satellite Coach (Yorkshire) Matt Paul.

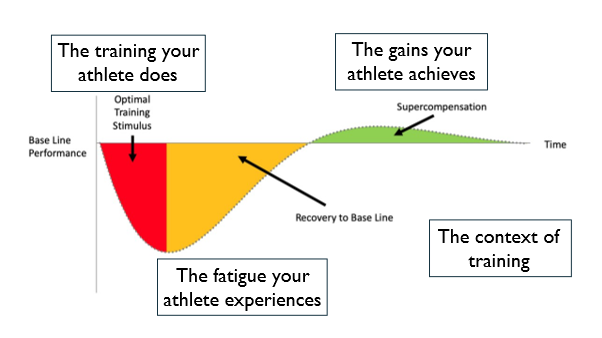

To recap on the first article in the series, monitoring can be split into four different areas, following the model of the training process itself:

- The context of the training

- The training your athlete does

- The fatigue your athlete experiences

- The gains your athlete achieves.

The previous article looked at the context of training and some elements of monitoring the training your athlete does. Here, we’ll look at more aspects of that.

The training your athlete does (Part 2)

Monitoring training load

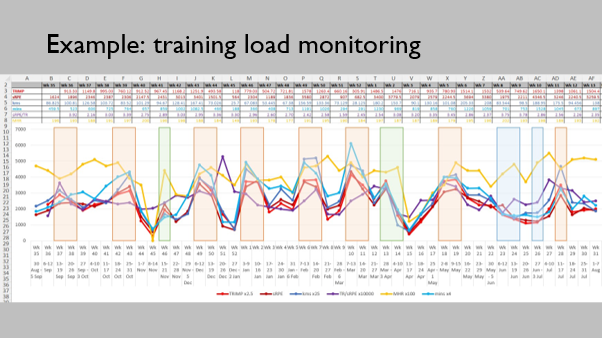

Here is an example of a training diary I developed, which was placed in a shared online folder and filled in individually by the athletes, containing all the elements described in Part 1. From the left you can see the external load, the outcome and the internal load.

The orange column to the right refers to Training Load, which is an attempt to quantify the load the training puts on the athlete. Training should cause positive adaptations in time, but in the short term it will cause the athlete to fatigue. The athlete will only progress if the balance between training load and fatigue is appropriate. The two methods I used here are based on heart rate and sRPE (RPE for a session overall).

sRPE is the simpler of the two, simply multiplying the duration of the session in minutes by the sRPE (using the 10 point Borg scale), then adding up the scores for all the sessions in a week.

The heart rate method, called TRIMP (training impulse), is based on an incredibly complex formula, and requires knowledge of both maximum and resting heart rates as well as the average heart rate for each session.

There are other methods, such as the T2 minute, which comes from Australia and involves summing all sessions, adjusting their duration according to the modality and the intensity to make them equivalent to on-water rowing sessions in Zone 2 of a five zone model.

These can be quite complicated, but luckily even simple metrics, such as total minutes or kilometres trained (shown below in light and dark blue) track pretty similarly (with a bit of adjustment of scales) to the detailed metrics (in red and dark red).

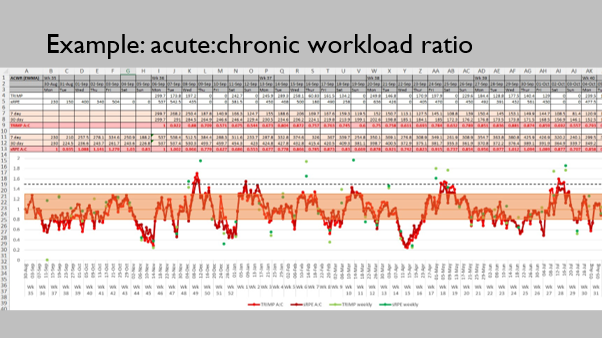

Another method of gauging the strain on an athlete is to look at the acute:chronic workload ratio. Essentially this compares how much training they are doing now with how much training they were doing a short while ago. A large jump might risk injury.

In the example below the athlete’s training generally keeps within the advised 0.8-1.3 range, rarely rising above the 1.5 warning level.

Monitoring strength and conditioning training

S&C training sometimes goes under the radar in terms of monitoring. In the gym it is still important that the training is appropriate, and that you gauge what fatigue the session will cause.

To ensure that the training that the athletes do matches the intention you have for the session, you need a sense of the intensity and volume of each exercise.

For developing strength, athletes need to be lifting over 80-85% of their single rep maximum (1RM), so for these sessions the load needs to be monitored. These loads don’t need to be taken to failure, so some method of ensuring the volume isn’t excessive is also necessary, such as Reps in Reserve (RIR), where the athlete would stop the set when they feel they are a certain number of reps away from failure.

For power development, the speed of the bar is important, and methods of tracking that are becoming more widely available, from linear position transducers (devices with a string to attach to the bar) such as GymAware, through inertial measurement units (devices that attach to the bar directly and can sense movement) like MoveFactorX, to phone-based apps such as Eliteform Tracker. The intensity would be set at a load that an athlete can move at a desired velocity. The drop-off in velocity over the set, either to a threshold velocity or as a percentage of the velocity of the first lift, can be used as a method to control the volume.

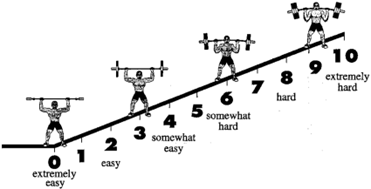

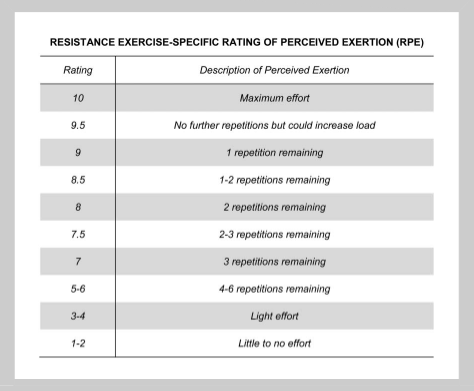

As with endurance training, it is possible to set intensity via the athlete’s perception. Several systems have been proposed, similar to the RPE scales. The OMNI-RES system is based on perception of load (below top), while another works on the Reps in Reserve concept (below lower). Force development work would sit at the top end of the scale, while power generation work would be more to the middle.

One benefit of perception methods is that they adapt to how recovered an athlete is when they arrive at a session, and accommodate adaptation through a block in the way that going on %1RM from a pre-block test cannot.

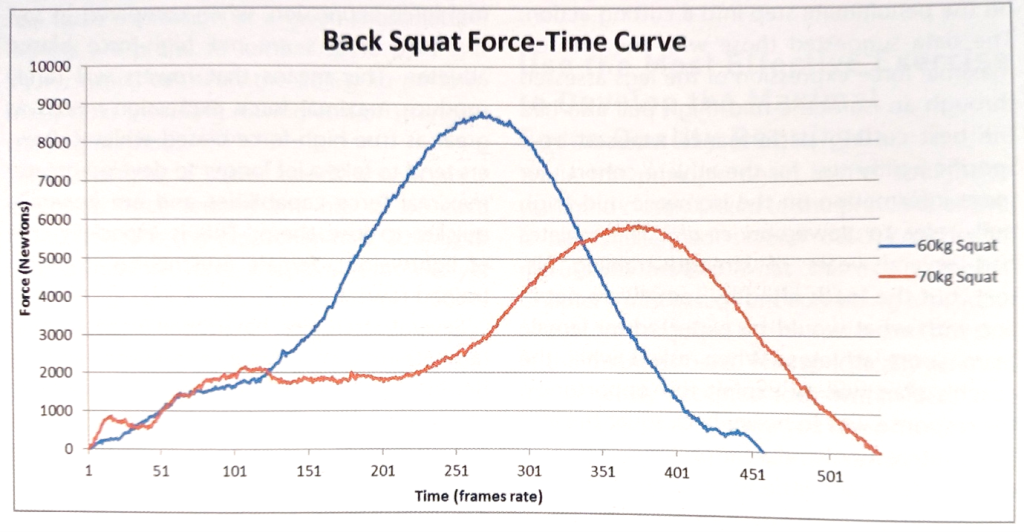

The question about all methods of monitoring strength training is that, referring back to the idea of external load, internal load and outcome as outlined in Part 1 with reference to endurance training, generally we look at the external load (weight on the bar, time under tension, etc) or the outcome (velocity of the bar), but not the internal load, which is the action of the muscles themselves. The fact that external and internal loads are not the same is demonstrated in the graph below, which shows that when lifting a lower load with better technique athletes can actually produce more force than when lifting a higher load badly.

Given that force is what the athlete produces, could it be this which is driving adaptation, rather than the load? And if so, how do we monitor that? Force plates are prohibitively expensive, and not practical in a squad scenario. However, it may well be that phone apps could calculate force soon, and wearable EMG sensors, which show the electrical stimulation of the muscles, are also becoming available.

There are several methods you can use to estimate the overall load of the session:

| Method | Measurement and calculation |

|---|---|

| Set Volume | Number of sets |

| Rep Volume | Number of sets x number of reps per set |

| Volume Load | Sets x reps x load |

| Relative Volume Load | Sets x reps x load as %1RM OR %Body mass |

| Work(-ish) | Sets x reps x load x distance load moved each rep |

For each of these methods you would calculate the score for each exercise, then add all the scores together for the session load.

Sadly, the quest for greater accuracy puts increasing pressure on data collection and analysis, without overcoming the issue that all methods fail to take everything into account that is important, such as bar velocity or rest durations. Technology might help, but the question is whether it can cover an entire squad for the duration of a session.

A possible solution is just to use the session RPE (sRPE) method, multiplying sRPE by the duration of the session, which would allow you to combine endurance and strength sessions easily within one overall training load model. The above methods could still have a use in estimating whether, upon changing the programme from one block to the next, the new session is roughly the same load as the previous one.

The next article in this series will look at the fatigue your athlete experiences.