This article is the first in a series on Monitoring and Assessment for Club Coaches by British Rowing Performance Satellite Coach Ben Reed. It’s based on a presentation he gave at the 2025 British Rowing Coaching Conference along with former British Rowing Satellite Coach (Yorkshire) Matt Paul.

Introduction

Monitoring incorporates anything that you can do to check on how your athletes are doing, and by extension the effectiveness of your coaching and programming.

Monitoring clearly covers testing, but given that training is what leads to testing results, it is important to monitor your athletes’ training as well. It is this knowledge that will allow you to learn what works if a round of testing is successful, or adapt your programming if necessary, as well as to individualise it.

When establishing your monitoring regime, determine:

- What you deem important in producing success

- What you have the ability to do in terms of time, resources, practicality, etc.

- What level of monitoring your athletes will support.

From this, you can select what to monitor, how, and when. You don’t have to be constantly monitoring everything. Not all forms of monitoring conform to the same timescale; some will be daily, others only seasonal. You could step it up at important times of the year, or perhaps when on camp and the athletes have more time.

For most sections, I’ve signposted a free and easy method of monitoring that’s accessible to club coaches with limited financial resources. However, I will also look at what else is available, even if that seems impractical or unaffordable, because there may be principles that can be adapted, and technological changes may soon bring these ideas within reach.

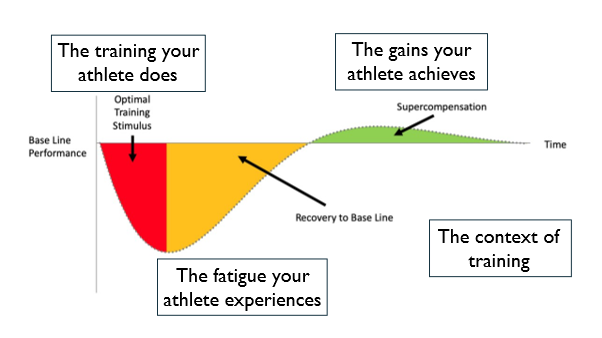

We can split monitoring into four different areas, following the model of the training process itself:

- The context of the training

- The training your athlete does

- The fatigue your athlete experiences

- The gains your athlete achieves.

The context of training

This section concerns aspects relating to your athletes’ readiness to train.

First, you could simply monitor attendance. Regular no-shows suggest that athletes are not enjoying or valuing the training. Equally, if an athlete is missing the same day’s training every week for unavoidable work or study reasons, are they missing the same element of training, and what could be done to cover that?

Tracking injuries can also reveal things about your programme. Do injuries cluster around the same time of the season? Do your athletes sustain similar types of injuries? Encouraging your squad to use the same physio gives you a valuable second perspective in this regard.

Finally, you could ask your athletes to monitor their hydration levels against urine colour charts, or what they are eating. Female athletes may benefit from tracking their periods to see if training needs to be adapted. Apps are readily available online for this.

The training your athlete does (Part 1)

Endurance training

You need to keep track of what training your athletes are actually doing. This can be done in various ways from paper training diaries to spreadsheets to online sites such as Polar Flow, TrainingPeaks and Strava.

In their diaries your athletes need to record three things:

- The external load: the training that is done (modality, distance/duration, rate, training zone, rest periods, etc).

- The internal load: how the athlete perceives or responds to the training (feeling, heart rate, lactate level, etc). Perception or rating of perceived exertion for the session (sRPE), is probably best recorded via the Borg Scale. The physiological response to exercise can be measured in different ways. Heart rate is the cheapest and easiest. It is accurate, detailed, non-invasive and gives real-time feedback, though can be affected by things like heat and hydration. Lactate levels and ventilation can also be measured, although the former is currently invasive and only capable of snapshots, while the latter has the impracticality of masks and pipes. Future technology, such as sweat lactate monitoring and more practical ventilation hardware, might solve these issues.

- The outcome: the score produced (velocity, split, power, etc). In on-water rowing, NK SpeedCoaches allow rowers to know rate and pace, impellors being more fiddly but more accurate than GPS. These can link with the Empower Oarlock to give force and power, as well as be downloaded for post-session analysis. Telemetry systems, while expensive, are becoming more prevalent, showing force curves, rather than just summary numbers. On the ergs the screen will give you all the information you need.

You can use this information in two ways.

First, you can see whether your athletes are training as you are programming. Clearly, if basic details such as modality or duration are not being observed, you would want to find out why.

However, intensity is not so easy for the athlete to observe, and is something that athletes can easily get wrong. Coaches can try to specify intensity by programming a rate, split or power output. But these may not be physiologically based, and fundamentally it is an athlete’s physiology you are trying to change.

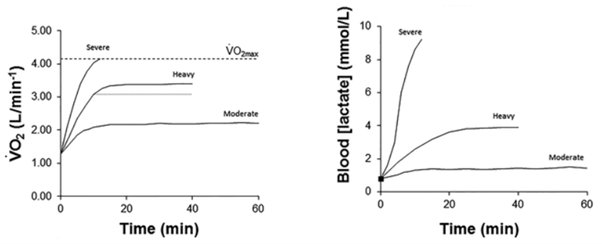

When exercising, three physiological outcomes can occur. If the intensity is low then minimal disturbance happens and everything remains stable. As the intensity rises there comes a point where disturbance happens, but the body is able to stabilise into a plateau at a raised level. Finally, if intensity gets too much, then further disturbance happens until a point where the body is no longer able to control things and soon exercise will have to stop. This gives us the basic three zone model of training intensity, as shown below.

Ventilation and lactate levels can reveal which of these zones an athlete is in, one in real-time, the other only at the point when the blood sample was taken.

Heart rate can also be tracked in real-time by the athlete, but does not in itself mark out these zones, so you need to have determined beforehand what rates equate to the physiological boundaries. Here are the boundaries based on maximum heart rate that the Norwegian Olympic Association uses (converting the three basic zones to five), though they are guides that would need to be individually tweaked. If nothing else is available, the guides of talking easily, talking with difficulty, and not able to talk might define the three zones.

| Zone 5 | Higher end of upper zone | 92-100% |

| Zone 4 | Lower end of upper zone | 87-91% |

| Zone 3 | Middle zone | 82-86% |

| Zone 2 | Higher end of lower zone | 72-81% |

| Zone 1 | Lower end of lower zone | 55-71% |

Second, having obtained that information, without resorting to testing, you can get an impression of whether the training is producing positive adaptations or not. Look for changes in the relationships between the three areas of external load, internal load and outcome. When doing this, make sure you bear in mind the context of the training. If, for example, you have a standard session that you repeat regularly (e.g. a 12k erg, r18), and there is less internal load (lower RPE and heart rate) and/or more outcome (lower split) for the same external load, things are going well.

In the next article in this series we’ll look at Part 2 of The training your athlete does, which will cover monitoring training load and strength and conditioning.

Photo: James Andrews