Crew selection is one of the most important tasks for a rowing coach. While some combinations just click, others take more time and effort to get right. Joanne Harris talks to club, university and school coaches about how they approach the challenge.

“Some rowers will never ever ‘get’ how hard it is for coaches to make that selection, how much stress it causes you. You really are trying to do the right thing, you’re not trying to do someone over,” says Royal Chester RC Senior Men’s Coach Jamie Leighton.

But where does the process of selection start, and what can coaches and athletes do to make the process as smooth and effective as possible?

Start from the beginning

“Selection starts basically on day one of the new season. The athletes are told this, that every day is selection day,” explains Durham University BC Head Coach Rob Dauncey.

“Selection starts basically on day one of the new season.”

Thames RC Women’s Head Coach Tom Mapp agrees. “During the first six months of a nine-month season it’s looking for those lightbulb moments, those real sparks of something cool and epic,” Mapp says.

But Mapp also cautions against selecting all the time. “Failure is a really good learning tool for all of us. It’s really important to let the athletes know when they’re being judged on all the performances and being super clear when the selection periods are and when they need to be on form all of the time,” he adds.

Data, data, data

Erg tests

Erg scores are the basis of the data collected by most rowing clubs around the country, with standard tests – especially a 2k – playing a key role in selection.

“It doesn’t matter how good you look on the water; if you haven’t got sufficient power you’re never going to move [the boat] enough”

“I’m very aware of how well somebody moves a boat, but I also know that it doesn’t matter how good you look on the water; if you haven’t got sufficient power you’re never going to move it enough,” Leighton says.

For this reason, one pragmatic approach when selecting eights, particularly in the head race season, is to select half the crew on erg scores and then seat race for the rest.

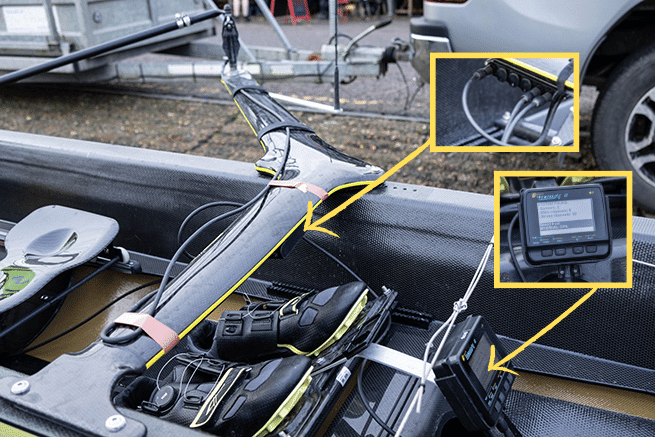

The role of telemetry in crew selection

What adds to raw power is technical improvements, and that is where telemetry comes in, as used by clubs including Durham and Thames. Telemetry systems collect power data from the pin, including watts, catch and finish angles, and power curves. In coxed boats, the cox can see all that data live. You can fix individual screens, rather like erg screens, to each seat so the rowers can see what they are doing, and some coaches will also have a mirror screen in their launch.

“We do the same work on the water that we do on the ergo. The first piece of data I then look at is how close somebody’s data is on the ergo to what they do on the water,” Mapp says.

Dauncey says his athletes enjoy learning from the data collected by telemetry, and he uses it as part of long-term ranking of rowers including in races.

“It’s good to have that data from a race situation as opposed to training situations because part of the thing you want to know is whether people are doing what you want to them to do as part of the race plan over the course of a race,” Dauncey explains.

On-water time trials

But telemetry is expensive and not every club can afford it. At Bryanston School in Dorset, Assistant Director of Sport Beth Rodford – a former world champion and Olympian for Great Britain – says their data comes from ergos and on-water time trials. The school, which has around 80 students rowing in years 10 to 13, trains on the River Stour, which generally has consistent conditions.

“There’s a lot to be said about individual boat speed leading to crew boat speed”

“We tend to do a time trial where we can on a Saturday in singles. There’s a lot to be said about individual boat speed leading to crew boat speed,” Rodford thinks.

Is seat racing the best answer for crew selection?

Seat racing is an element of crew selection, but coaches value it as much for what it tells them about an athletes’ mental attitude to racing as about the data gathered – which can often be flawed, due to conditions, a crew over-rating, and so on.

Leighton admits he has in the past got seat racing wrong; Rodford says Bryanston does not have the capacity to do it.

Mapp says seat racing does not take into account the lives rowers have around rowing, adding: “If you do too much seat racing you find somebody’s 90% speed more than who’s got the top-end speed.”

Looking for the spark

Once you’ve taken data into account and rankings are becoming clearer, you also need to consider how well a rower fits into a particular boat, and what extras they might bring. Athlete input can be useful here, especially where selection is close.

“You really have to look at the athlete as a whole rather than pick one single data point.”

Dauncey says the majority of selection is objective and data-based, but personality and technique can come into play, especially lower down the rankings.

“You really have to look at the athlete as a whole rather than pick one single data point. You also need to know yourself as a coach and reflect on what your strengths and weaknesses are in judging people to make sure that you’re not just focusing on the stuff you like,” Mapp says.

Rodford says someone who can steer, or unites a crew through personality, can sometimes bring the most value.

“If they bring the crew together that’s worth far more than a couple of seconds [of individual boat moving] from somebody else,” she says.

This is why all the coaches interviewed for this piece say selection is a continuous process of testing combinations to find what makes a crew tick, and looking at how they move a boat or move with the crew.

Some rowers may be better suited to the middle of an eight rather than stroking a coxless four; others stronger scullers than sweepers. Athletes also develop at different rates, so someone who is at the top of the squad by the Head of the River Race might find themselves overtaken by Henley.

“I experiment all the way through, pretty much to when entries close for Henley Royal Regatta,” Dauncey says.

Honesty in selecting crews

When it comes down to announcing crew selection, honesty is always the best policy.

“I never want selection to be a surprise to anyone. I want to have had a couple of discussions with them beforehand, just so that they know where they stand,” says Rodford. “When you’re dealing with younger athletes ,they have so many pressures on them from elsewhere in the school. Often sport is their safe zone, you want it to be a positive experience.”

Dauncey recommends using the data gathered through the year when selection is queried by an athlete. “If you have all the information then it isn’t a challenge, it’s facts, not opinion and not emotion,” he says.

“Where they’re selected has no impact on how [an athlete] should see themselves as a person or affect their self-worth.”

Both Leighton and Rodford say selection can be harder in smaller squads because there is a shallower pool to pick from. Mapp, however, thinks that squad size makes no difference and environment is key. “You need to be really honest and let the athletes know the selection has no weighting on your support and caring for them. Where they’re selected has no impact on how they should see themselves as a person or affect their self-worth,” he adds.

“As a coach it’s super-important for you to make sure you are trying to let them know you have their best interests at heart.”

Whatever the size or type of club, crew selection is about making the fastest possible boats. But it’s also essential that the process makes sure that rowers who put in so much time and effort feel that effort is valued and recognised.

“I’m just really keen that they have fun. For me it’s about passing on that love of rowing that I’ve had. I’d love them to get even a tiny bit of that,” concludes Rodford.

Banner and telemetry photos: Joanne Harris