Exmouth rower Graham Hurley and crewmates have been rowing twice a week for 12 years. There have been plenty of moments to treasure, but one of his all-time favourites is how they first became the Vulcaneers

Picture the scene. We’re four oarsmen and a cox in search of an air show. It’s a while back, 2009, and the weather is forecast to be well within limits.

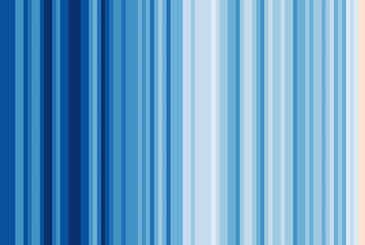

Our plan is to stock our trusty Safran with goodies to eat and drink, launch from Exmouth beach, and row three miles down the coast until we can sit comfortably off Dawlish and enjoy a huge variety of Boy’s Own treats from vintage biplanes to the Red Arrows and the rumoured appearance of the nation’s sole remaining Vulcan bomber. This, believe me, is a beast, a flying manta ray the colour of death. On a sunnyish August afternoon against a tumble of perky clouds? Irresistable.

Alas, the weather refuses to obey the script. As a regular crew we rotate the coxing, and it happens to be my turn. Out beyond the big offshore sandbank, it’s much rougher than we’ve expected and we quickly agree that bouncing around for the remains of the show will be no fun. Accordingly, I ride the wave train shorewards. Already, the beach and promenade at Dawlish are black with spectators.

Only when it’s far too late for second thoughts do I realise that the breaking surf is going to be a handful. Pete Bradshaw, at stroke, warns me of the next oncoming wave behind us. I ride it with some success, approaching the beach at speed, but – alas – have no time to extract the rudder. We land in one piece, safe from the reach of the next wave, nearly intact. Our one casualty? The rudder.

“The air is suddenly full of exhaust-howl, followed by a thin drizzle of coloured smoke, but we’re smashing out through the waves”

We haul the boat onto its side and examine the damage. The rudder is history. We happen to have coincided with a lull in the flying programme, and hundreds of watching spectators are taking a lively interest in our little drama. Cleverly, we appear to have trapped ourselves on a shrinking beach, against a rising tide. Within a couple of hours there’ll be no sand left. Our only option therefore is to extract the remains of the rudder, haul the boat round, and launch into surf that is getting meaner by the minute. Dave McDermott and Pete Bradshaw sort the rudder, after which we decide on a snack and a think.

The flying, as ever, is spectacular, and my daughter-in-law’s cheese and chilli sandwiches are even better. Kate, alas, has understandably no interest in staying with us for the return trip and so my son is summoned at short notice. He’s a big lad. Getting off the beach in one piece will demand maximum revs.

By the time he’s turned up, we’ve hatched a plan. None of us have any appetite for coming to grief in full public view but happily we have just enough beach left to wait for the arrival of the Red Arrows. Our calculation is simple. The vast crowd on the prom will be watching the Red Arrows, not us. And so we ready the boat, and wait.

As ever, the Arrows burst into the party without knocking. Heads tilt skywards, while young girls cover their ears and scream. Our launch is in the hands of Les Norcliffe, a nerveless ex-marine. We’ll have, he tells us, just one chance to get this thing right. He doesn’t take his eyes off the incoming waves. On his cue we pile into the Safran and pull for our lives. This happens to coincide with a low pass from two converging Arrows, just inches above our heads. The air is suddenly full of exhaust-howl, followed by a thin drizzle of coloured smoke, but we’re smashing out through the waves, still alive, still intact, and everything appears to be going remarkably well. I’ve never been in a shooting war but this feels very close.

“And there she is, our sole remaining Vulcan, flanked by six Red Arrows, flying directly over our heads”

A minute or so later, maybe a hundred metres offshore, we’re all euphoric. Pete Bradshaw, at stroke, is using one of his blades Kon-Tiki style as a rudder and no one appears to be missing the real thing. We’re still congratulating Les on the launch of a lifetime when he nods at the sky behind us. “Gentlemen…” he’s grinning, “….just look.”

And there she is, our sole remaining Vulcan, flanked by six Red Arrows, flying directly over our heads. I swear the pilot is waving, and even if he isn’t it doesn’t matter. From now on, thanks to those amazing heart-in-the-mouth three minutes, we’ve become the Vulcaneers.

Since then, twice a week, all year round, we Vulcs have rowed a distance equivalent to two crossings of the Atlantic. Guest rowers have come and gone, but the core of the crew has remained the same. Our collective age in the boat is currently 357 but in our sillier moments we have plans to double that. Rowing has brought us wonderful craic, a passion for tide-cheating, a passport to some of the finest water in the kingdom, and a lifetime’s supply of unforgettable moments. But nothing – so far – to match that peerless Vulcan.

Photos: Peter Todd