Train hard in the winter and you could reap the rewards when summer racing comes. Coach consultant Robin Williams explains how profiling your racing can help and provides advice

The question of race profiling might seem a strange subject to tackle right now as we are in January with Covid still interrupting proceedings, but to race well next summer relies on getting a few ingredients sorted now, months ahead. The very idea of profiling a race at all demands a certain sophistication and an understanding of your physiology and technical level.

Plenty of people approach it much more vaguely: just do some fitness work in the winter, some sharpening up in the spring and then get stuck into the regattas and see how it goes!

Profiling means taking a proper look at your target races, working out what is needed to win, and then being honest about where you are now, and how to tackle the performance gap. If you don’t do this then your choice of profiles will be pretty much limited to ‘do a start and hope for the best’!

To choose how to pace a race you need options: explosive power, good aerobic endurance, effective power-to-weight ratio, a strong muscle chain, and of course exemplary technique! Some of these need months to train, others just a few weeks.

The real investment needs to be in the mid-race pace – finding the ‘red line’ marking the outer range of our aerobic fitness

Racing brain

You also need the brain for it and the ability to flex your planned profile if the situation demands it tactically. The Oxford-Cambridge Boat Race, or any racing match, is a good example of this, but a head race is a chance to profile exactly as you want, as indeed is a rowing machine test.

Any race, whether 2,000m or long distance has the same basic phases to it: start, transition, mid-race, and finish, so we need to train physiology, technique, mental strength and tactical awareness all in parallel.

No one has a problem giving 100% to the start because you are fresh. Raising a finish sprint is always possible because the end is in sight, but this is largely a gamble. If your opposition are better drilled, have more fast twitch muscles, a better lane, or have had fewer races, they may well get there first. It is a last-chance card. Making expensive tactical pushes are a bit the same, even though they are sometimes necessary. The real investment needs to be in the mid-race pace – finding the ‘red line’ which marks the outer range of our aerobic fitness.

Mid-race

This part of the profile takes time and effort to build, but a robust middle 1,000m in the summer means we can sometimes avoid the need for fancy attacks and finish sprints. However, it can be hard to do the long steady training at a good enough quality – very often the combination of low rate and high volume causes the stroke cycle to be slow and ponderous. We get a general physiological benefit but not the technical accuracy. This means it can be a struggle to convert hard steady miles into functional race speed.

Muscle acidity

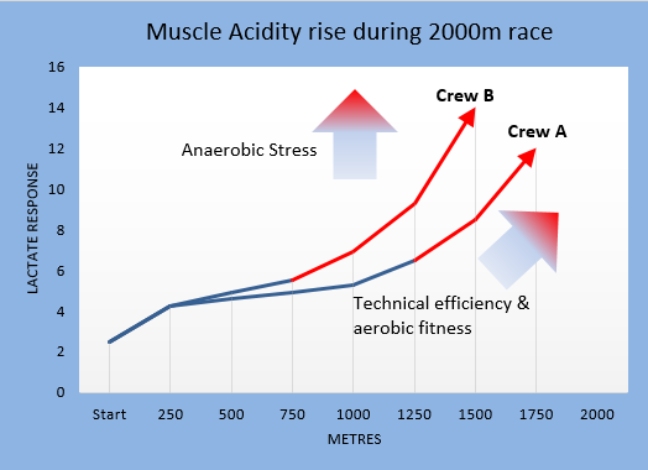

Let’s look at the physiological part of this: the graph below is a theoretical profile of a typical 2,000m race and shows what happens to the levels of waste products in your muscles as you race down the track.

Physiologists look at multiple parameters, but increased acidity in our bodies will be a familiar feeling to all who race – it starts to hurt! Muscles burn, oxygen is in short supply, and we know that time is running out before we seize up. The onset of this feeling is most obvious in the third quarter.

Sitting on the start, however, lactate levels will be a comfortable 2-3 mmol/L (millimoles per litre of blood) depending on the warm-up we’ve done. When we race off, our breathing and heart rate respond quickly to the exertion because the muscles instantly ask for more oxygenated blood.

The first minute of effort will cause a small spike in the lactate response while our aerobic system catches up, but it will steady for a while after that because there is a lag between the work done and the consequence in the muscles. The longer we maintain the intensity, the more it increases, climbing through 5,6 and 7 mmols and heading sharply up as fatigue really mounts. This contrasts with steady aerobic training where we can comfortably clear the blood lactate while we are training and stay between 2-4 mmol/L.

Those precious metres might make the tactical difference we need, where the opposition begin to crack, and we do not

The red line

We can see on the graph that the line steepens up significantly at 1,000m then 1,250m and 1,500m as we go into the third quarter. This is a hypothetical situation, not a real graph, so the actual values will vary with individuals, but it illustrates the point: if we have not done enough aerobic fitness in the winter then the ‘bite’ point will come sooner.

In our example, crew B experiences this around 750m whereas for crew A, it comes nearer 1,250m. If technique is not good, the effect is the same because the inefficient use of our physiology brings the stress point earlier in the same way.

In fact, we often see this phenomenon, where a field of six crews is quite bunched to 1,000m and then in the following minute the gaps will appear. Interestingly, it often looks like the best crews have pushed on, but it is usually because the others have slowed. The better our technique and aerobic base, the more of our speed can come from this source.

If we can go fast enough without pillaging our anaerobic reserve too much, then the upward deflection point will be pushed back by maybe another 200m or so. Those precious metres might make the tactical difference we need, where the opposition begin to crack, and we do not.

Six tips and solutions

1. Use the start

Don’t waste your start speed: a lot of crews are good at going fast over the first 10 strokes, but lose the speed again soon after by failing to move athletically with the boat. They get heavy and tight with it. Equally bad is to keep the sprint going for too long because you will pay back later on for this, with interest.

2. Carry your speed

So, the transition is key. Those first 10 strokes should create a surplus of hull speed, around 110% of your average 2km speed.

The next 20 strokes should see you ride that wave of speed by being powerful, but relaxed and accurate. To move from sprint to race pace it is better to ‘push on to rhythm’ rather than lift off the accelerator or drop rate. Press out the finish and avoid over-reaching at the front – effective length is better than length for its own sake.

Practise points 1 and 2 by sometimes rowing off a bit above pace for 10 strokes and then transition to your training rate (but keep the speed!).

Examples to look at include the famous NZL men’s pair of Eric Murray and Hamish Bond, who often lay in third to sixth place at 500m

3. Red line pace

This is the theme of this article: not easy to do, but the second 500m needs determination and trust in that winter fitness.

The top international crews try to minimise fade to 2-3 seconds here and then maintain this over the middle 1,000m. Practise this discipline in steady winter training too: watch your boat speeds and even aim for negative splits, ie get faster in the second half of a session, not slower. You can apply this to your work on the rowing machine too.

4. Mental toughness

Level split profiles take courage because you may not lead in the first minute or two.

Examples to look at include the famous NZL men’s pair of Eric Murray and Hamish Bond, who often lay in third to sixth place at 500m, second or third place at 1,000m, but led at 1,500m and won by clear water. The other boats slowed in the mid-race where they held speed.

The Irish lightweight men’s double at the 2019 Worlds were sixth, third, first and first in their gold medal race and showed great pacing judgement, based off technical and physical confidence. With match racing this profile is less common but does sometimes happen. You can pressure the other crew quite nicely whilst sitting half a length down – sometimes!

The rowing machine… is a good measure of physical output so you know the split you can maintain

5. Technical accuracy

The entry and the catch in the winter need to be as precise as in the summer – the entry just puts the blade in the water; the catch simply compresses the face against the water. They shouldn’t be half the speed just because the rate is half and are more about anticipation and synchronisation than actual speed or power. This will help keep the dynamics of the long miles really crisp and give the muscles and neural pathways the right kind of training stimulus. Lowering the drag factor on the rowing machine occasionally can be good for producing faster muscle contractions.

6. Rowing machines and head racing

Profiling on a rowing machine is quite simple. You do not lose energy through timing errors with other crew-mates, nor do you find a ‘heavy boat’ because you have lost your entry/catch coordination.

The rowing machine lacks skill, but is a good measure of physical output so you know the split you can maintain, and this can teach us something useful for the boat.

Some years ago, my London Rowing Club lightweight crew applied their 5k rowing machine pacing to the 7k Head of the River eights on the Tideway.

Instead of ‘blast off and hang on’ which was the crude wisdom of that era, we carefully measured our delivery and used rate capping for the first half to avoid over-pacing. From the start to Hammersmith Bridge, the crew behind had closed two boat lengths on us, but from Hammersmith to the finish we took 11 seconds off them and finished third overall.

To Hammersmith, it meant the focus had to be on the processes: power per stroke, distance per stroke, and accurate technique. From Hammersmith Bridge to the finish we were racing for the result. This is just an example of how the physical, technical, mental and tactical all come together when the starter says ‘Go’ and was a very worthwhile experiment in profiling.

Exercise resources

For more resources, don’t forget to check out our Rower Development Guide pages here, plus you can see our exercise library here.

If you’ve attended a British Rowing coaching course, there are videos available of some of the skills and drills, as well as a selection of free posters on conditioning, available to download from RowHow.

Thanks to Dr Mark Homer and Sarah Moseley for their expert advice.

Illustration: Robin Williams and photos: Naomi Baker, Drew Smith