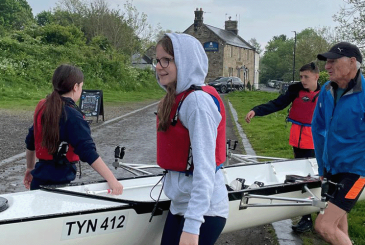

How can you learn to adapt your style to your athletes? Coach Consultant Robin Williams explores different coaching styles and what they mean in behavioural terms

Many years ago, I came to the end of my international rowing career and was encouraged by Penny Chuter, the then Head Coach of British Rowing, to go on a British Rowing coaching course. As a newbie coach I was instantly struck by the value of training theory, physiology, biomechanics, and sports science.

I thought, ‘If only I had known more about this while I was still a rower, I would have been so much faster!’. It helped make sense of many of the mistakes I’d made over the previous 20 years and was both fascinating and frustrating. But it still had a missing ingredient: it did not tell me how to coach.

Your own experiences only go so far and do not make a perfect template for everyone to follow, but I did find that the passion you have as an athlete is equally important as a coach and that brings us to coaching styles and how you get your knowledge across.

You may have an encyclopaedic knowledge about rowing theory but if you cannot make it work in a live situation, or lack energy and leadership, then you could be a great trainer but possibly not a great coach. So, knowing ‘what’ to do for training and the basics of a rowing stroke is of course important, but ‘how’ you get it across is the human face of the process.

There are coaches who don’t know everything, but who are very good at inspiring the rowers towards their goals and can facilitate their journey with energy and enthusiasm, creating the right environment referred to in previous articles. So, a coach can pick up the knowledge, but can you learn style?

It would be reasonable to think that, like teaching style, parenting style, or business style, it is simply ‘you’. It is just your natural personality; so, some people are loud, tough, and demanding, others more conversational and collaborative, some fun and friendly, and others distant.

Just as rowers have gaps in their prowess, so do coaches.

Coaching and leadership studies have identified at least three styles – authoritarian, democratic, and casual

Coaches are there to help rowers overcome their gaps but who develops the coaches? That requires some deeper thinking and I meet a lot of coaches on technical workshops around the UK who know what they need to know, but have yet to fully develop their delivery. Often, they have been left to work this out for themselves. This is, rightly, an evolving journey but there are several approaches that coaches can cite in order to formulate a style that suits them and their athletes.

Coaching and leadership studies have identified at least three styles – authoritarian, democratic, and casual. Each one has advantages and disadvantages, and individuals will naturally sit somewhere on that continuum.

The first one is quite easy to recognise and has produced a lot of success in rowing and other team sports. The coach is a task master, direct, decisive, and insistent. The training is tough, and the individual athlete support is limited. There is plenty of ‘what’ instruction and the coach might say, “Today you’re doing 16km at rate 20 with a target boat speed/pulse of… and it’s side-by-side”.

Those basic facts give the rower plenty to work with, but it’s a journey of exploration and finding out. If you cannot handle that work, get fitter! If you can handle it but the speed is too low, get tougher or maybe row better! It will breed resilience and a surviving mentality in the group which may very well help win races. It can create a high energy in the group too.

The potential downsides, however, are that some people need more explanation, discussion, and ‘tweaking’ of the programme towards their particular needs. There can also be injury, under/over-training, or just lack of enjoyment if that kind of regime is not for you. This style tends towards strong coach knowledge, but low coach-athlete support.

It is interesting that some key Olympic sports created their success with a firm management style. If you are losing, then perhaps there’s not much room for democracy – you just make the tough decisions and focus hard on the outcomes you want.

Years later though it is noteworthy that some of these sports, having gained the success, have subsequently been tarnished with allegations of bullying coaching styles, so clearly all coaches need to strike a balance between the toughness needed to win and the focus on the athlete as a person.

The second style of coaching, democratic, can still be strongly led at the front, but is more about collaboration, taking the athletes with you and guiding them as partners. Instead of obediently following they are afforded the information to understand, give feedback and have input with the coach, so it is easy to see that this respectful approach could motivate many rowers, especially those who have already learned to train hard and tough. This style tends towards strong coach knowledge and strong coach-athlete support.

The third style – casual – is possibly the least helpful to rowing, but not without value. It puts the athlete firmly in charge and is a much more laissez-faire relationship. If you were a mature athlete, possibly training alone or in a small group, then it’s possible that is what you need from the coach. It might suit the more recreational rower with less of a focus on competition. This style tends towards low dependency on coach knowledge and low coach-athlete support.

Record some of your coaching and listen to yourself a few days later – be your own critic!

The conclusion we reach is that we should probably coach with elements of all three styles rather than being pigeon-holed to just one, and should adjust our approach according to the kind of club we coach in, and what level and type of rowers we work with.

Formal coaching courses find it hard to teach the coach how to adjust style: it’s largely a matter of common sense and seeing what works.

I remember being impressed by my coaching mentor, Harry Mahon (NZL and CUBC), and experimented with what I thought was the same style as it seemed very effective. The rowers, however, found my ‘new style’ rather odd – it just wasn’t me!

Nevertheless, a great way to develop your own style is to coach alongside another coach. It tends to be obvious very quickly if they have captured the attention of the crew and the session is going well, so you can compare and contrast this with your own communication.

If you can enter into a genuine mentoring situation and give, and receive, feedback as a coaching team, being able to critique – but without causing offence – then this is really powerful and very educational. A next best thing is to record some of your coaching and listen to yourself a few days later – be your own critic!

Structure and content of training sessions are part of coaching style

Whatever style you adopt, certain things hold true for all good coaches, I believe. Pushing athletes is fine because we all like the feeling that the coach thinks we are capable of more. It is a compliment, even if it is hard to do. Planning and organisation are important, so keeping to the point and making sure the sessions run efficiently minimises time wasting. Distance – don’t try to be everyone’s friend because you might have to give them the news that they have lost their seat one day! You can be warm, fair, and respectful and treat everyone evenly and rowers will develop trust based on that.

In terms of how you deliver the session on the water, I like the idea that there is a narrative, like a book chapter. In each session we want to achieve something, be it physically, technically or in mental experience.

Begin with the briefing that outlines the structure of the session, so the crew knows what is in your head and what standard you expect. Include the distance, work and any of the ‘what to do’ information.

Have a main theme: for instance: ‘control towards the catch’. Then explain the warm-up because this is how we begin to unlock the ‘how’ – the technical and mental approach to the training. Observe the warm-up and see if, indeed, they are engaged based on your briefing. What does their concentration and body language look like? The coach wants athletes to be curious, ambitious and even fascinated by the session.

Be prepared to adjust the session as you go, if necessary (eg if conditions change, the technical goal isn’t working) and in the democratic or collaborative coaching style, say there’s nothing wrong now and then ask for their views about the session afterwards. They know what is going on inside the boat!

When tackling a technical goal, it is important to explain:

1. What you see as the problem

2. What you see as the cure

3. What will be the benefit – without a benefit there’s no incentive to change.

When you get off the water and rack the boat, the final thing is to debrief – briefly. Try to sum up what they did well, what direction we want next time. This bookends the session and is important, but very often people want to rush off due to time pressures. It’s about squaring the circle, so that your views and theirs tally.

So, structure and content of training sessions are part of coaching style – they give a sense of authority even if you are not a naturally authoritarian person. Asking questions and getting feedback makes you more open, even if you are not naturally collaborative. Perhaps, once in a while, allowing athletes to suggest the content for the session is casual even if you are not normally like that.

On and off the water it is important to be consistent and build a relationship, so that athletes and coaches understand each other and there is a good ‘fit’.

If you are interested in personality and leadership styles look at Insights Discovery and also Athlete Assessments, run by Bo Hanson, former Australian Olympic rowing medallist.

Photos: John Anderson, Stuart Gordon and John Stead