In a new series on approaches to technique, Coach Consultant Robin Williams explores how you can create an inclusive environment and training programme where everyone can flourish.

If you were a coach starting a new job at a rowing club what would you take with you on day one – a stopwatch and a megaphone, or a broom, pen and paper? I’d choose the latter because the first thing I’d do is make sure the place looked clean and tidy, then I’d write a welcome note for the rowers about to arrive, and then a training plan to put on the club noticeboard.

Now this is obviously a metaphor for creating the right environment in the club, but a sense of order, a mood of enthusiasm, and a shared plan are really important ingredients in the running of a successful programme.

It is easy to see technique too as something which just starts in the boat but without the right environment it will count for little.

I don’t mean necessarily the physical environment, although there’s nothing wrong with a fancy gym, new boats, and great facilities. No, I mean the human environment which incorporates the way your club ticks, its atmosphere, people’s attitudes, how smoothly it runs, the sense of mission and collective enthusiasm, plus how connected it all is. It has a material effect on the quality of your rowing.

When you all don your club racing suit it truly means something and is a form of branding; the club colours representing all the hard training you have done, your technical excellence, togetherness, and high standards. Any rugby team confronted by the All Blacks and the Haka do well not to feel intimidated because they always represent tough opposition, and everyone knows how tough it is to earn that jersey and defend their own high standards.

The bottom line is that you have to back yourself and believe in the way you row

This will sound like a truism, I know, because who would want to exist in a club where people constantly turn up late, the place is messy and disorganised, the boat you planned to use has been taken by another crew, seats are often missing, oars incorrectly geared, there’s no real outing plan, no technical theme and no debrief after to say whether we did something good, okay, or below par.

It would be an uninspiring environment to be in and, so, when you finally get on the water and the coach is trying to improve technique, the rowers may not be ‘on receive’ for the message because the tone has already been set to accept indifference, poor standards and limited expectations.

And yet, these situations do arise and more commonly than you might imagine – it isn’t that anyone means it to be this way, in fact I often say to coaches that no one goes out on the water intending to row badly, but sometimes they do!

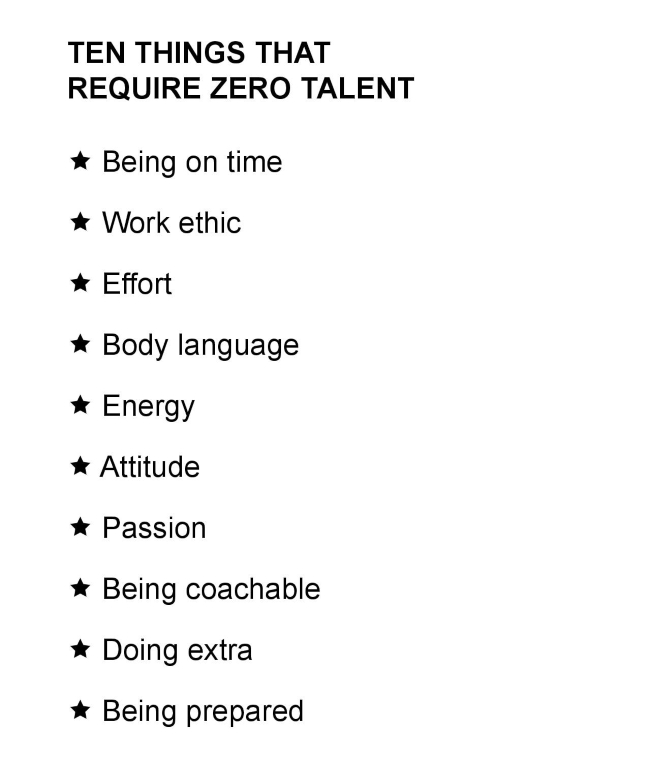

Equally well, no coach intends to go out and coach poorly, but sometimes that happens too. Usually, it is just that the leadership is not clear enough, there isn’t enough organisation, and the group inherits a certain culture in the club which continues to perpetuate until someone finally stops still and challenges the way it is being done. The ’10 things that require zero talent’ is a reminder how some simple principles go a long way if adopted by everyone. It is easy to imagine really good, purposeful training sessions with people like this compared to the other version just mentioned.

Clubs tend to have their ups and downs and even giants like Leander have experienced this in their history, so when confronted with a failing programme, the environment is the very beginning of creating a turnaround.

The turnaround began by redefining the underlying principles for the group

The Boat Race has run since 1829 and the historical wins and losses have often run in sequences, sometimes two or three, occasionally much longer such as Oxford University Boat Club (OUBC) in the 1970s and 1980s under the strong leadership of iconic coach Daniel Topolski when they won 16 out of 17 years. He embedded values of toughness, quality, and team spirit which the students bought into and success became a conveyor belt as older students brought on the newer ones. The rowers were as much custodians of the OUBC technique and culture, as Topolski himself, and made sure they initiated the younger ones, so they in turn could pass it along.

When Cambridge finally stemmed the tide, it was largely because that particular generation of students had re-set their own parameters on thinking, training and technique with the new coaches Sean Bowden, John Wilson, and Harry Mahon bringing fresh ideas and determination.

In other words, the turnaround began by redefining the underlying principles for the group and, from that, stemmed the precise detail of the training programme and the technique. The bottom line is that you have to back yourself and believe in the way you row. There are many other examples – Nottinghamshire County Rowing Association built an equally impressive club culture in the 1980s and 1990s, Imperial College under Bill Mason in the 1990s and Oxford Brookes (OUBC) is a great example in recent times.

Of course, a good rowing environment has all sorts of benefits for a club, school or university rower way beyond a Boat Race or Henley win. It can have a huge impact on everyone’s enjoyment of the sport and can help you take good habits into other parts of your life.

Spratley admits that initially the programme was rudimentary, just plenty of training and a fierce attitude towards racing

OBUBC makes a good case study for anyone trying to build a great programme. Under Richard Spratley’s strong personality, Oxford Brookes began with almost nothing, just a second-hand eight on a trestle in a field. Thirty years on, they have two boathouses, a fleet of top boats, a large and thriving membership and Head Coach Henry Baillhache-Webb, an ex-OBUBC rower himself, has built on the model even further.

Asked about their formula for success they immediately stress the importance of culture and setting the tone with everybody taking pride in the club, whichever boat you end up in.

Spratley admits that initially the programme was rudimentary, just plenty of training and a fierce attitude towards racing, but over time more attention has gone into developing technique, and other performance elements, all helping maintain their string of successes, which incidentally includes 41 Henley wins, and numerous BUCS’ victories, under-23 and senior GB vests.

Let’s now climb into our boat and go rowing.

With everyone punctual and on-task, the crew knows what they are aiming for with the session and when the coach presses for more they are willing to give, curious to find out, happy to take risks and learn from mistakes, reinforced by an encouraging atmosphere in and out of the boat.

Indeed, technique is as much about thinking, as it is about doing. A few simple themes may be all you need. For instance, ‘we’re all going to focus on letting the boat run’, ‘we’re going to use the finish as a strong timing reference for everyone’, ‘we’re going to be aware of our mass over the stretcher at the front’ and so on.

Technique is as much about thinking, as it is about doing

No real technical detail there, but if everyone thinks along those lines then it usually happens that way. Some programmes do surprisingly well with little technical direction, but a very strong culture, and use athletes to bring on athletes and training scenarios to create the conditions for learning.

This is because the best way to learn how to move a boat is being in one with better people than yourself. The second-best way is to be in a boat alongside a better crew and learn from that situation. The third-best method is to be with no other boat – but have a well-meaning coach with a megaphone trying to describe in words the nuances of boat-feel while you are simultaneously working hard, steering around bends, coping with weather, noise and other distractions!

I am admitting this as a coach myself, so it is pretty disappointing, but coaching is as much about creating the environment as technical detail, so it’s no wonder that it all begins on land when you arrive, on time, and smiling!

Photo: Oxford Brookes University BC